Australia’s ‘watergate’: here’s what taxpayers need to know about water buybacks

by Head of UniSA’s School of Commerce, Professor Lin Crase

ENVIRONMENT AND SUSTAINABILITY An aerial view of a drought ridden section of lagoons on the River Murray. Photo: Shutterstock

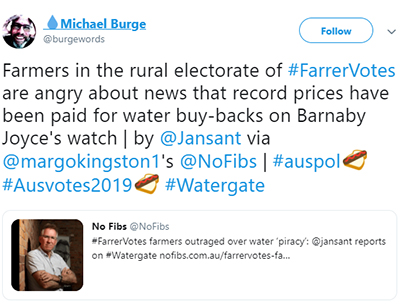

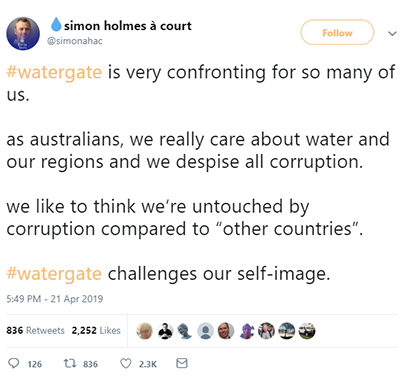

ENVIRONMENT AND SUSTAINABILITY An aerial view of a drought ridden section of lagoons on the River Murray. Photo: ShutterstockIn 2017, the then agriculture minister, Barnaby Joyce, signed off on an A$80 million purchase of a water entitlement from a company called Eastern Australia Agriculture.

UniSA Head of School: Commerce Professor Lin Crase

UniSA Head of School: Commerce Professor Lin CraseThe problem is that Energy Minister Angus Taylor used to be a director of Eastern Australia Agriculture – though he didn’t have a financial interest – and the company is a Liberal party donor. What’s more, the value of the water purchased for A$80 million is under question.

Now, as the election looms, this issue has resurfaced. But why should taxpayers be concerned?

Water buybacks using an open tender were halted by the current Government in 2015, even though this is the most cost-effective way to set aside water for the environment. Instead, the Government pronounced that subsidies for irrigators were a better deal.

Until 2015, the Government bought back most water using an open tender process, before it was replaced by a subsidy scheme for irrigation and occasional closed tenders.

The problem with the closed tender process is that it tends to lack transparency, which raises questions about how effectively the Government is spending public money. And it’s hard to prove closed tenders deliver the most cost-effective outcome.

The Murray-Darling Basin is a very productive agricultural zone and its rivers have been used to boost agricultural outputs through irrigation.

State governments spent much of the 20th century allocating this water to agricultural users. By the 1990s it was clear too much water was being extracted. This resulted in both harm to the river environment and potential reduced reliability for those with existing water rights.

Various attempts to rein in extractions were made around this time, but ultimately the Murray-Darling Basin Plan was adopted to deal with the problem.

In agreeing on the plan, the Federal Government committed to spending A$13 billion to reduce the amount of water being extracted from the Murray-Darling Basin. To accomplish this the Government has two basic strategies.

One involves buying up existing rights for water use. The other hinges on using subsidies so farmers use less water when irrigating.

Reducing water extraction from the basin

The second approach of using subsidies is generally more politically appealing. This is because few farmers ever object to receiving a subsidy and the public has an affinity with the idea of “saving” water.

The problem, however, is that subsidies are a more costly way of returning water to the river system than simply buying back existing water rights. And so-called water savings are hard to measure – how much water savings are a result of subsidies or some other factor?

This is why some analysts even claim subsidies are reducing the level of water available for the environment.

Buying back water rights is generally more cost-effective than providing subsidies. But a clear and transparant process still matters because water rights are not the same for everyone and it’s a complex process to determine their overall value.

Allocations and entitlements

First, most water users hold a legal right, known as an entitlement. Water entitlements represent the long-term amount of water that can be taken and used – subject to rain, of course.

Second, water allocations represent the amount of water currently available against a given entitlement – this is the water that is available now.

If a farmer owns an entitlement in the River Murray, chances are the annual allocation will be determined by how much water has flowed into upstream storages like Hume Dam, Dartmouth Dam or Lake Eildon.

Even then the allocation will vary, depending on which state issued the original entitlement. For instance, New South Wales water is generally allocated more aggressively. This means NSW entitlements tend to be less reliable in dry years than Victorian or South Australian entitlements.

If a farmer owns an entitlement where there are no upstream storages, as is the case with much of the Darling River system, then the allocation will vary depending on how much water is flowing in the river.

So what?

All of this means the amount of water that can actually be used for the environment when an entitlement passes to the Government will depend heavily on the underlying characteristics of the water right.

Partly for this reason, water buybacks were historically conducted using an open tender process.

This meant the Government would announce its willingness to buy water entitlements. Farmers would then notify the Government about what entitlements they held and the price they were prepared to take.

Running an open tender allowed the Government to assess the value for money of the different entitlements on offer at the time.

Water buybacks through open tender began seriously in about 2007 to 2008. This meant the price owners were prepared to sell for would be registered, and then the Government would determine which offer provided the best value. Around 60 per cent of all water now held for the environment by the Commonwealth was secured through open tenders.

As a general rule, a relatively high-reliability water entitlement was bought for about $2000 per megalitre and this has become the metric for many in the market. But the current Government halted this process in 2015.

Now, the Government buys water through direct negotiation with water-entitlement holders.

The Government justified ending open-tender buybacks on the basis that the water being secured was causing undue harm to rural and regional communities. And, instead, much more expensive subsidies would supposedly generate a better overall return.

This view is not universally shared. The receipts from openly tendered water entitlements were being used by many farmers to adjust their business, while still staying in the region.

Many rural communities continue to thrive, regardless of the strategy chosen to secure water for the environment. Subsidies also tend to favour particular irrigators rather than the community in general.

Having set aside the cheapest option of open-tender buybacks and declaring support for irrigation subsidies, the problem the Government now faces is that it must explain why closed tenders persisted (albeit in isolated cases) and were signed off by ministers as good value for money.

Closed tenders need not deliver a poor outcome for taxpayers. But it does mean the likelihood of establishing the best value for money is reduced, simply because there are fewer reference points.

And if it’s legitimate to overspend public money on irrigation infrastructure subsidies, the credibility of a supposedly cost-effective closed tender is also brought into question.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Other Stories

- How many cups of coffee increase your risk of high blood pressure, heart disease?

- The art of the circus: Cartwheeling kids to better mental health

- Engineering students’ future careers through upgraded facilities

- World Solar Challenge to test new energy strategy for solar industry

- From the Vice Chancellor

- Achievements and Announcements

- Are you getting enough sleep?

- How your brain can fake pain

- Australia’s ‘watergate’: here’s what taxpayers need to know about water buybacks

- Exceptional achievements acknowledged in first graduations of 2019

- Cancer researchers join bike tour pedalling towards a cure

- Defence and the bench: the cause of dwindling football scores

- The latest books from UniSA researchers

- In Pictures