Why you should learn the Kaurna phrase Yangadlitya Kumangka

By Adam Joyce

People who identify as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander are advised that this article contains names of people who have died. Seeing the name of someone who’s died may be upsetting or distressing in some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, and in some situations, offend against strongly held cultural prohibitions.

COMMUNITY Kaurna and Ngarrindjeri man Isaac Hannam performs a smoking ceremony for the UniSA Enterprise Hub. The Kaurna name for the UniSA Enterprise Hub, Yangadlitya Kumangka, was bestowed by Uncle David Rathman AM, PSM, FIML at a special naming ceremony, on behalf of Senior Elder Uncle Lewis AO and the Purkarninthi Elders in Residence. The name was the generous gift of the Kaurna Warra Karrpanthi – the leading group dedicated to Kaurna language revitalisation and maintenance.

COMMUNITY Kaurna and Ngarrindjeri man Isaac Hannam performs a smoking ceremony for the UniSA Enterprise Hub. The Kaurna name for the UniSA Enterprise Hub, Yangadlitya Kumangka, was bestowed by Uncle David Rathman AM, PSM, FIML at a special naming ceremony, on behalf of Senior Elder Uncle Lewis AO and the Purkarninthi Elders in Residence. The name was the generous gift of the Kaurna Warra Karrpanthi – the leading group dedicated to Kaurna language revitalisation and maintenance.For many years, it was said that the original language of the Adelaide Plains, the Kaurna language (Kaurna Warra), has been sleeping.

But slowly and steadily it is being revived and reclaimed, largely through the work of Kaurna people and language specialists.

Kaurna Elder and leader Uncle Lewis Yarlupurka O’Brien AO has been a key part of that work. He was a member of the Kaurna language group Kaurna Warra Pintyanthi (KWP), which was formed in 2002 to promote and restore the Kaurna language.

Uncle Lewis says it’s a long journey, but there’s now momentum with wider recognition of Kaurna words and an increasing number of people able to speak the language.

“We are patient – we say, when it’s ready, it will come,” he says.

In 2013, the language committee Uncle Lewis was part of, decided to establish a sister organisation with formal legal standing, to support the reclamation and promotion of the language of the Kaurna nation, including training and teaching.

Kaurna Warra Karrpanthi (KWK) is an independent Aboriginal not-for-profit organisation. Its role includes requests for Kaurna names, phrases or translations.

Translating a word between English and Kaurna might sound straightforward but it often isn’t.

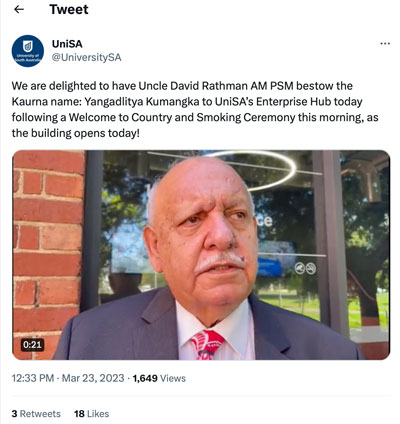

Uncle David Rathman AM PSM, FIML, who bestowed the Kaurna name Yangadlitya Kumangka to UniSA’s Enterprise Hub, explains the significance of the name.

Uncle David Rathman AM PSM, FIML, who bestowed the Kaurna name Yangadlitya Kumangka to UniSA’s Enterprise Hub, explains the significance of the name.While tangible entities such as body parts, artefacts and animal names often have direct equivalents, abstract concepts are extremely difficult to translate. Aboriginal languages are based around very different metaphors and conceptual notions than in English.

Kaurna uses many suffixes (word endings that alter the meaning). A common suffix is nindi.

“Nindi means becoming or transforming into – it’s a twist which English can describe but can’t do,” Uncle Lewis says.

The word warra means forest, so warranindi means transforming into a forest.

“Language is a gift and there are concepts in Kaurna language for which there’s no equivalent in English,” Uncle Lewis says. “Learning an Aboriginal language opens your mind to new ways of thinking and teaches you to think laterally, in a similar way to how philosophy is associated with Greek and mathematics with Indian.”

By the mid-1800s, the Kaurna people had been driven out of their land and settled in missions at Poonindie (Eyre Peninsula), Burgiyana/Point Pearce (York Peninsula) and Raukkan/Point Mcleay (Lake Alexandrina), where they were forbidden to speak and share their own languages. It is believed the Kaurna language was last spoken in a day-to-day context in the 1860s although many Kaurna practised it in secret.

“I was lucky that I learnt a bit when I was a kid,” Uncle Lewis says. Uncle Lewis was born at Point Pearce Mission in 1930.

Kaurna people feel a strong sense of ownership over their language and ask that people use the Kaurna language with respect. Part of Kaurna Warra Karrpanthi’s role is to record language use.

How UniSA’s Enterprise Hub got its Kaurna name

Uncle O’Brien liaised with Kaurna Warra Karrpanthi on the Kaurna name for the UniSA Enterprise Hub in Light Square.

“On behalf of the University, I asked the language committee [Kaurna Warra Karrpanthi] for permission to use the words Yangadlitya Kumangka, which means for the future, together,” he says.

“Our people worry about the future for their kids and grandkids. It’s important for our people to learn about their culture and for their language to be used as part of the knowledge base for future generations. Aboriginal language is a gift so that’s the philosophy behind the name … for the future, together, Yangadlitya Kumangka.”

At a special smoking ceremony in late March, the UniSA Enterprise Hub was officially gifted the name Yangadlitya Kumangka.

UniSA Deputy Vice Chancellor: Research and Enterprise Professor Marnie Hughes-Warrington AO says the name is a beautiful phrase and “for the future, together” is a wonderful way of describing the University’s approach to partnership.

“Kaurna philosophy teaches us that we do not learn just by hearing or looking at what others do. We take the second step, as Senior Elder Uncle Lewis puts it, when we act on that knowledge,” Prof Hughes-Warrington says.

“We learn in the present, bringing our past experiences, but that second step is into the future. Yangadlitya, for the future. This epitomises the spirit of UniSA, the university of enterprise. For enterprise means a promise, together.”

If you’re interested in learning the Kaurna language, visit the Kaurna Warra website, for more information. An English to Kaurna dictionary (Kaurna Warrapiipa) is also available.

About the Kaurna language

The Kaurna language is the original language of the Adelaide Plains. It was last spoken on a daily basis roughly around the 1860s. Though speakers of the language undoubtedly survived long after that date, Kaurna People had few opportunities to speak the language because of policies and practices that restricted the language and prohibited use in public. Most of what we know of the Kaurna language comes from senior Kaurna men (Mullawirraburka, Kadlitpinna, Ityamaiitpinna and others) who were recognised as leaders by the colonists in the 1830s. Their language was recorded by two German missionaries, Clamor Schürmann and Christian Teichelmann, between 1838 and 1857. A range of other observers recorded wordlists of varying length and quality, but Teichelmann and Schürmann were the only ones to write a Kaurna grammar. All in all, about 3000 Kaurna words were recorded in historical sources. Some areas, such as body parts or verbs related to speaking, were fairly well documented, but there are many gaps. It is likely there would have been at least 10,000 Kaurna words. However, we are not restricted to these 3000 words, because quite a lot is known about how words were formed in Kaurna. The Kaurna Warrapiipa: Kaurna Dictionary contains an additional 400 new and repurposed words to fill in some of the gaps, following traditional Kaurna word formation processes. For instance, we now use warraityati for ‘telephone’ (literally ‘the voice sending thing’). For more information on the reawakening of the Kaurna language see Warraparna Kaurna! Reclaiming an Australian Language (Amery 2016) available as a free download.

Source: Kaurna Warra Karrpanthi

Other UniSA buildings with Kaurna names

- Pridham Hall has been granted a Kaurna language name, recognising its place and purpose on Kaurna land. Its Aboriginal name is Yangkadlitya Wardli, which means for-the-future building.

- The Bradley Building has been honoured with a Kaurna name, Purruna Wardli, which means Healthy Place.

- Yungondi Building

- Kaurna Building

Other Stories

- Australian teachers at breaking point as budget delivers superficial support

- Substandard rental housing a threat to resident health and wellbeing

- Why you should learn the Kaurna phrase Yangadlitya Kumangka

- The WHO says we shouldn’t bother with artificial sweeteners for weight loss or health. Is sugar better?

- From the Vice Chancellor: Universities Accord – What’s the big idea here?

- Achievements and Announcements

- Mother and son pair celebrate graduation from Aboriginal Pathway Program

- From Foundation Studies to PhD and beyond

- Accolades for two influential Aboriginal voices as UniSA endorses wider principle

- In Pictures: MOD. holds its biggest party yet + National Reconciliation Week

- The latest books from UniSA researchers