"It's in our air, soil, water and food": UniSA researchers investigate how forever chemicals make their way into our bodies

Chances are, you’ve, ingested, inhaled or absorbed 'forever chemicals' through your skin. Known as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), these synthetic chemicals, found in the environment and consumer products around the world, have been linked to adverse health outcomes, such as decreased fertility and an increased risk of cancer. Thankfully, UniSA researchers are working to understand factors influencing PFAS exposure and approaches for risk mitigation.

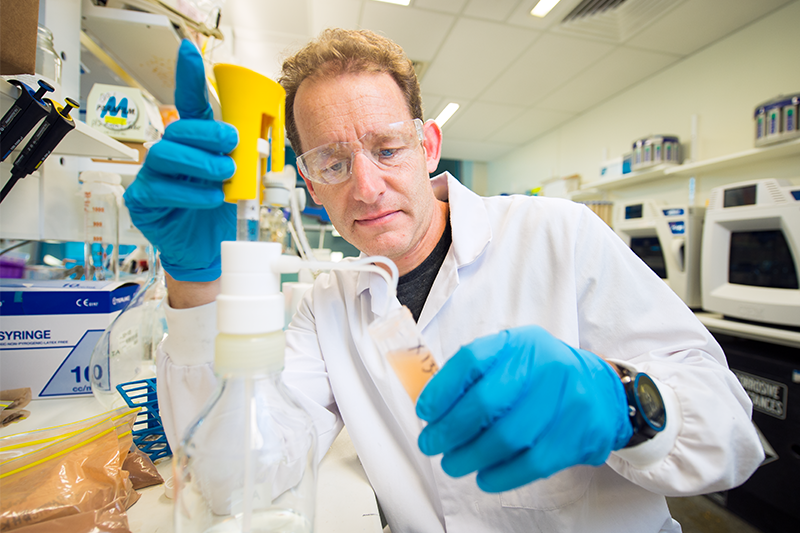

UniSA researcher Professor Albert Juhasz, with over 25 years of experience studying environmental contaminants, is internationally renowned for his innovative research on how substances like PFAS can be absorbed by the body.

“PFAS are known as 'forever chemicals' because some of them do not break down in the environment or in our bodies,” Prof Juhasz says.

“Considering this, the presence of PFAS in soil, water, air and dust, their potential to transfer to food – and their prevalence in consumer products – is quite confronting, as it risks human exposure.

“Understanding the amount of PFAS people take into their bodies—and why—will certainly help paint a clearer picture of its implications for human health. Importantly, this knowledge will also inform strategies for reducing exposure".

Prof Albert Juhasz

“PFAS are also found in some firefighting foams, which historically have been used around the world in mine sites, airports and defence bases1.

“Higher levels of PFAS have indeed been detected in the air, soil, and water in these areas.”

Overseas governments are beginning to impose stricter regulations on these chemicals; France will soon ban the manufacture, import and sale of most products containing PFAS2 while the US Environmental Protection Agency has recently set legally enforceable drinking water limits for PFAS3.

In Australia, the National Health and Medical Research Council has recently proposed to reduce the current accepted levels of PFAS in drinking water4.

These proposed new drinking water standards for PFAS are based on new information about potential adverse health effects.

Prof Juhasz, and his fellow researchers at UniSA’s Future Industries Institute have recognised a fundamental knowledge gap regarding the assessment of PFAS exposure.

They are working to address this gap and provide further understanding on the impacts of PFAS.

Caption: UniSA is examining PFAS exposure from soil, dust and food to understand how these compounds are absorbed, metabolised, distributed and excreted.

“We need to better understand exposure, including factors that influence PFAS bioavailability—the extent to which PFAS is absorbed into the body,” Prof Juhasz says.

“Currently, we’re collaborating with the South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute (SAHMRI) to examine PFAS exposure from soil, dust and food to understand how these compounds are absorbed, metabolised, distributed and excreted.

“Understanding the amount of PFAS people take into their bodies—and why—will certainly help paint a clearer picture of its implications for human health.

“Importantly, this knowledge can also inform strategies for reducing exposure and help shape public health initiatives, community education and government policy.

“We also hope our work will aid in developing physicochemical and nutritional strategies that could effectively minimise PFAS exposure.”

Learn more about the Future Industries Institute.

[1] What are PFAS? Australian Government

[2] French lawmakers vote to ban 'forever chemicals' expect in cooking utensils, Le Monde

[3] Final PFAS National Primary Drinking Water Regulation, United States Environmental Protection Agency

[4] Australian Drinking Water Guidelines 2024 PFAS, The National Health and Medical Research Council