12 April 2023

South Australian scientists have documented the catastrophic decline of a stand of red stringybark in the Clare Valley, a tree species that has survived in the region for 40,000 years but is now at risk of extinction due to climate change.

Two severe droughts driven by climate change since 2000 are blamed for “staggering losses” of an isolated population of the South Australian species Eucalyptus macrorhyncha in the Spring Gully Conservation Park.

Multiple surveys led by University of South Australia environmental biologists Associate Professor Gunnar Keppel and Udo Sarnow have recorded tree and biomass losses of more than 40 per cent, during the Millennium Drought from 2000-2009 and the Big Dry from 2017-2019.

More than 400 trees were monitored over 15 years, within two years of their dieback first being reported in 2007.

The scientists say that approximately 250 tonnes of biomass per hectare have disappeared.

“In areas that experienced complete dieback, drooping she-oaks remain as the only trees, suggesting that the red stringybark ecosystem could be replaced by a more open woodland,” Assoc Prof Keppel says.

The research team, which included scientists from the State Herbarium of South Australia and University of Adelaide, has published their findings in the journal Science of the Total Environment.

Genetic data show that the red stringybark trees in the Clare Valley have been isolated from their closest relatives in the Grampians National Park in Victoria for about 40,000 years. This predates the Ice Age when Australia was much drier and cooler.

“The Clare Valley provided a safe haven that facilitated the survival of the red stringybark during this arid period. However, current climate change is different from the last glacial age. It is associated with much hotter temperatures compared to the preceding time periods, which were cooler but much drier.”

The team used trees marked by the Department of Environment and Water to document the progress of the eucalyptus dieback in the Clare Valley.

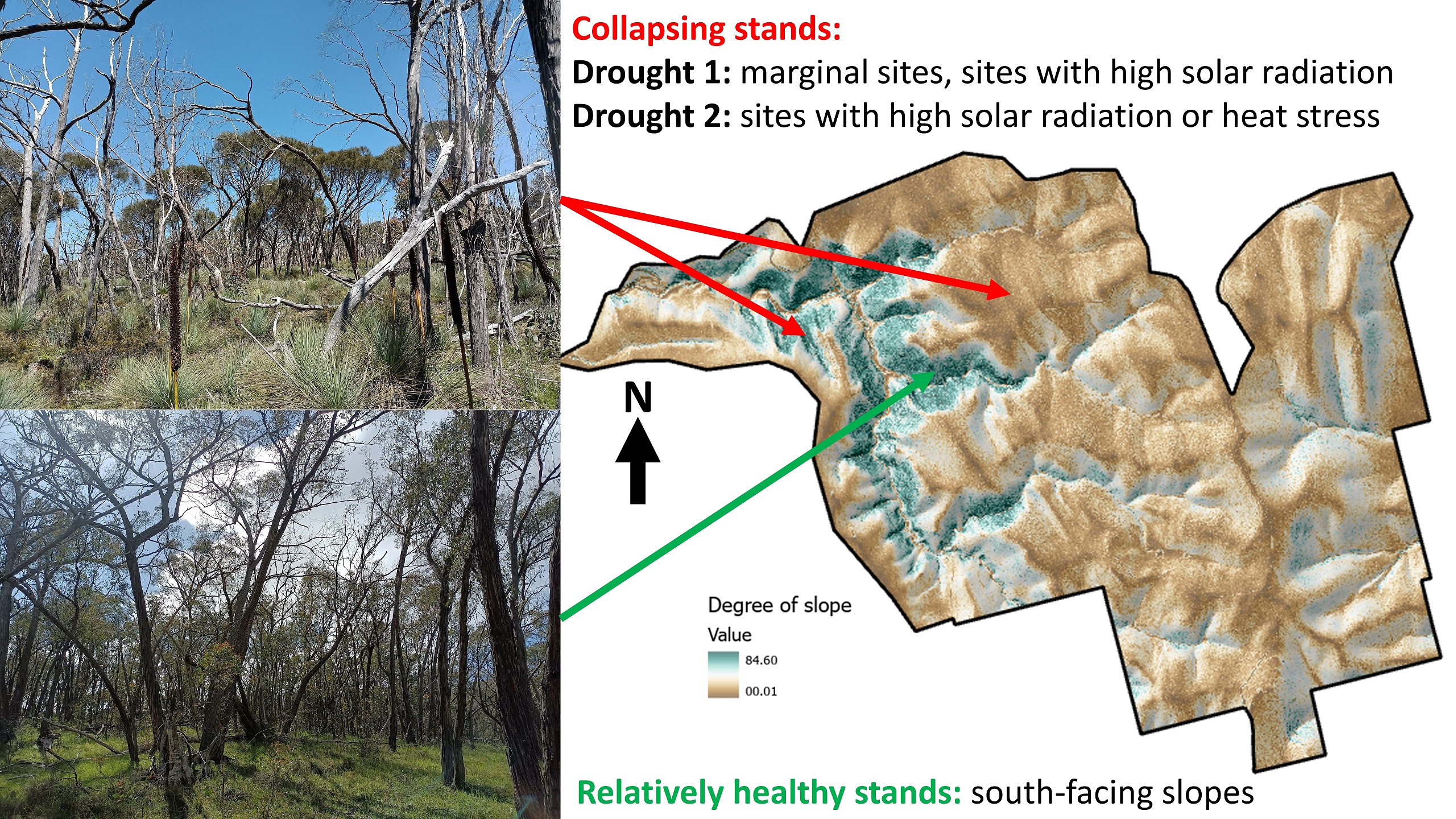

During the Millennium Drought, sites with less water and on flatter ground were most severely affected, while sites subjected to the greatest heat stress were most susceptible during the Big Dry.

Dieback is further compounded by intensive agriculture and viticulture in the Clare Valley, potentially adding more stress and preventing migration to sites that may facilitate the species’ survival.

But there is hope, researchers say.

“Mortality was much lower on the south and east-facing slopes – sites that received less sun and therefore less heat and drought-stress,” Sarnow says.

“In these locations, some regeneration was also evident. Hopefully, the population can persist in pockets that provide milder microclimates.

“If we can manage the population in Spring Gully Conservation Park, protecting these microclimates, we may be able to save this unique element of Australian biodiversity.”

Notes to editors

“Population decline in a Pleistocene refugium: Stepwise, drought-related dieback of a South Australian eucalypt” is published in Science of the Total Environment.

Udo Sarnow completed this research as part of his Master of Environmental Science.

For a copy of the paper, email UniSA media officer candy.gibson@unisa.edu.au

Contact for interview: Udo Sarnow E: udo.sarnow@posteo.org

Media contact: Candy Gibson M: 0434 605 142 E: candy.gibson@unisa.edu.au