17 August 2020

When UniSA architecture researcher, Dr Julie Collins, sat down a couple years ago to begin writing a book on the history of health and medical buildings, she could never have predicted the global situation she would eventually release it into.

When UniSA architecture researcher, Dr Julie Collins, sat down a couple years ago to begin writing a book on the history of health and medical buildings, she could never have predicted the global situation she would eventually release it into.

“I wrote a whole chapter on quarantine stations,” Dr Collins says, “and while I was writing it I was thinking how much those buildings were a relic of another time – now you look around the world, and we’re recreating very similar set ups in hotels to try to control coronavirus.”

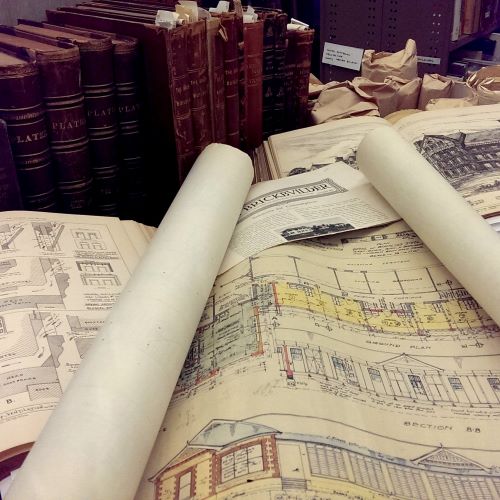

Dr Collins is Collections Manager at UniSA’s Architecture Museum, and through the course of writing her new book, The Architecture and Landscape of Health: A Historical Perspective on Therapeutic Places 1790-1940, she encountered striking similarities between the current pandemic crisis and historical struggles against disease and illness.

“When you look at health crises like the tuberculosis pandemic in the 1800s, before we had pharmaceuticals and biomedicine, really ‘place’ was one of the only ways we could prevent and counter the spread of communicable diseases,” Dr Collins says.

“The approach was to isolate ill people in dedicated sanatoria that provided fresh air, good nutrition, rest and exercise, all under medical supervision.

“Then when we developed pharmaceuticals – these kind of magic bullets cures – a lot of those ideas fell by the wayside, which is a pity, because as we can see now, they are still relevant to the isolation principals we’re falling back on in the absence of other effective treatments.”

Given the striking similarities between pandemics of the past and the one currently gripping the planet, Dr Collins suggests there is much to be learned from historical health buildings and the philosophies, theories and circumstances that influenced their design.

“Many therapeutic places, such as sanatoria, quarantine stations, and even asylums, were created to try to battle afflictions that were really poorly understood at the time,” Dr Collins says.

“But they were also guided by the best medical science of the time, and by the best intentions, and many of those insights are still valid now.

“The architects of these places realised the importance of ventilation, windows that could be opened to allow fresh air and natural light, as well as the importance of keeping distance between people and providing proper sanitation.”

While these design principals might seem simple and obvious to many people today, Dr Collins suggests they have fallen out of practice in some important contemporary situations, and the coronavirus crisis might serve as a reminder of how important these design considerations are.

“I think, in particular, if you look at some of the designs we now use in our workplaces, such as offices and manufacturing, then a lot of our contemporary designs have neglected ventilation, access to sunlight and access to nature,” Dr Collins says.

“Coronavirus might lead us to re-examine aspects of many workplaces, as well as the areas associated with them – what we call third places – the coffee shops and other small social places we use during our working lives.”

Dr Collins’s research suggests that, through history, our built environments have always responded directly to the challenges of illness and disease, often with far reaching implications, and there is every reason to believe this pattern will continue.

“For example, following the rapid urbanisation of the population during the Industrial Revolution, we began building city parks, both as ‘urban lungs’, but also through the recognition that mental health was aided through exposure to nature and exercise and social interaction,” Dr Collins says.

“Also, the whole modernist movement in architecture and design – the clean lines, open spaces, minimalist styles – developed as an extension the principals of hygiene and sanitation that guided early hospitals and public health buildings.

“So, history shows the challenges of health and illness really influence the way we build the world around us, and I think that will continue to happen into the future.”

Media contact: Dan Lander

Phone: +61 408 882 809

Email: dan.lander@unisa.edu.au