06 September 2019

It is increasingly common to use robots in war zones to examine and disarm hazards or recover objects with the understanding that the loss of a robot is a far more acceptable outcome than the death of a solider.

It is increasingly common to use robots in war zones to examine and disarm hazards or recover objects with the understanding that the loss of a robot is a far more acceptable outcome than the death of a solider.

But as robots become valuable members of the team, there’s a tendency to treat them like colleagues rather than machines.

University of South Australia Professor of Human Computer Interaction, Professor Mark Billinghurst, has collaborated with Dr. James Wen and other members of the United States Air Force Academy (USAFA) to explore these connections and their impact on team efficiency and productivity on the front-line.

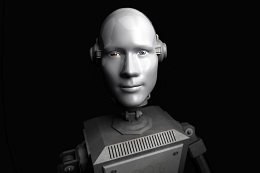

Their research shows that for robots to be fully integrated within a human-machine team (HMT), they first must be accepted as teammates. To facilitate this, a lot of work has been done over the years to make robots more ‘human-like’ by altering their physical characteristics and capabilities.

While humanising robots strengthens the working relationships between soldiers and their robots, it also inflates the value of the robot team members in the minds of military personnel, leading to an increased emotional response when the robot is put under stress.

Designing a simulation-based application, researchers tracked the emotional responses of two teams of participants who undertook a range of simulated tasks with either a personified or non-personified robot.

The study showed that teams working with a personified robot were 12 per cent less likely to put their robot at jeopardy of destruction compared to teams working with a non-personified robot, and that they were more sensitive to the robot’s health and the possibility of seeing the robot ‘killed’ in action.

This is the first time that research has measured how actions can be altered by empathy when potential harm is induced in a simulation.

Prof Billinghurst says the results show first-hand how emotional connections can impact decision making in the field.

“We have evidence to show that teams working with a personified robot are significantly more mindful about limiting damage and harm towards it – but this can have significant consequences,” Prof Billinghurst says.

“Participants who limited their use of robots or chose not the use the robots had a similar overall achievement to the teams that did, the result of an increased level of self-sacrifice in the form of working harder to gain the same result.”

For most of us, an emotional attachment to a robot is considered harmless. Creating a bond with your Roomba vacuum or Google Home speaker can be fun and comforting, but empathy shown by a solider towards a military robot has the potential to interfere with performance on the front-line.

“Rather than sacrificing the robot, participants who were working with a personified robot had to increase their workloads and were willing to take more personal risks and would stop before putting the robot at risk – impacting their decision making under pressure,” Prof Billinghurst says.

“Such hesitation and having an empathic response in these circumstances could have dangerous consequences for military personnel.”

Where split second decisions can determine the difference between life and death, it will become increasingly important to monitor soldiers working in collaboration with robots.

It is expected that military robots will be increasingly used in the future necessitating further research, training and evaluation on the topic.

The research also has implications for a wide range of other human/robot collaborative tasks in non-military settings, such as on the factory floor, in hospitals, or even in the home.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………................................................................

Media: Annabel Mansfield: office +61 8 8302 0351 | mobile: +61417 717 504

email: Annabel.Mansfield@unisa.edu.au

Lead Researcher: Professor Mark Billinghurst office: +61 8 8302 3747 | Mark.Billinghurst@unisa.edu.au