20 December 2022

Johanna Jarvis

Meditation professional

Founder, The Light Inside

Bachelor of Arts, Journalism/Politics

Already balancing a high-pressure career in news media when personal tragedy struck, alumna Johanna Jarvis was forced to take better care of her inner well-being. What followed was a career change which has taken her on an unexpected path all the way to New York City’s notorious Rikers Island.

Graduating from the University of South Australia in 1990, Johanna (Joh) Jarvis worked her way from newspapers into radio as a reporter, executive producer, content director and Senior Executive. In her 25 plus years as a journalist, she has held roles in regional Australia, in the Northern Territory, Melbourne and Sydney.

“I think if you want to get somewhere (as a journalist) you need to be prepared to move,” says Joh. “If you go to a small place, you can do more, you get more responsibility than you would in a large centre. So, it's great to go to places like Darwin, Alice Springs, all of the regional areas.

“I got to report on some really important Aboriginal issues, like the Mabo decision. I was really fascinated by Aboriginal affairs, and really fortunate to be able to cover those stories.”

While based on the east coast, she covered the 1998 Waterfront Dispute, the establishment of the Kennett government in Victoria as well as the Howard government on a federal level.

“But my brother died around that time, and I was just very sad. Work seemed meaningless … so I quit.”

After taking some time travelling in Asia, Joh returned to ABC Local Radio in Melbourne as a senior producer, eventually running the station at an editorial level. Later she went to Darwin to run the station and its outposts in Alice Springs and Katherine.

Two years later she was running the ABC’s 24-hour radio news service out of Sydney. It was a demanding role which exposed some underlying emotional issues that hadn’t been resolved after her brother’s death. “I was anxious and depressed,” she says. Neither of these conditions was diagnosed yet they had major impact on her well-being.

Preferring non-medical treatments, Joh cleaned up her diet, got some therapy and practiced yoga every day, but it wasn’t until someone recommended meditation that things started to improve. “I immediately felt peaceful. Obviously, things don’t change overnight, but I knew that this was the answer.”

“I was just in a dark place – the worst years of my life. My life is really good now, but it’s because I started meditation, it absolutely resolved the anxiety and depression. Therapy was also important and works so well in conjunction with meditation.”

Joh eventually trained as a meditation teacher, graduating in India in 2013, she then started teaching others, including a number of ABC colleagues. “Generally, people who teach meditation have experienced some pain in their life. When they find meditation helps enormously, they often want to share it with others,” Joh says.

While things were on the up – she was feeling good, approaching 50 and had a successful career, a nice house – Joh began to wonder “what’s next?”

“I'm not relentlessly ambitious – I always look for the meaning in things. And I used to ask ‘what’s the point of all this’. I would write stories that had a big impact, lead the bulletin or the program I was working for, but I was left wondering if there is any impact from what I’m doing? Am I actually making a difference? I felt I had more I could do in the world.”

So, she followed a dream to move to New York City, where she knew no-one.

Torn between establishing both a freelance journalism career and a meditation business in a new country, she sought the advice of her own teacher and mentor, who became a trusted friend. He asked her whether there was a cohort she would love to teach. Joh was interested in teaching meditation in prisons but felt she should focus on growing her business teaching in Manhattan before working with incarcerated people. “He said ‘no, you have to go with what’s in your heart – that’s where the drive will come from’. He was right!”

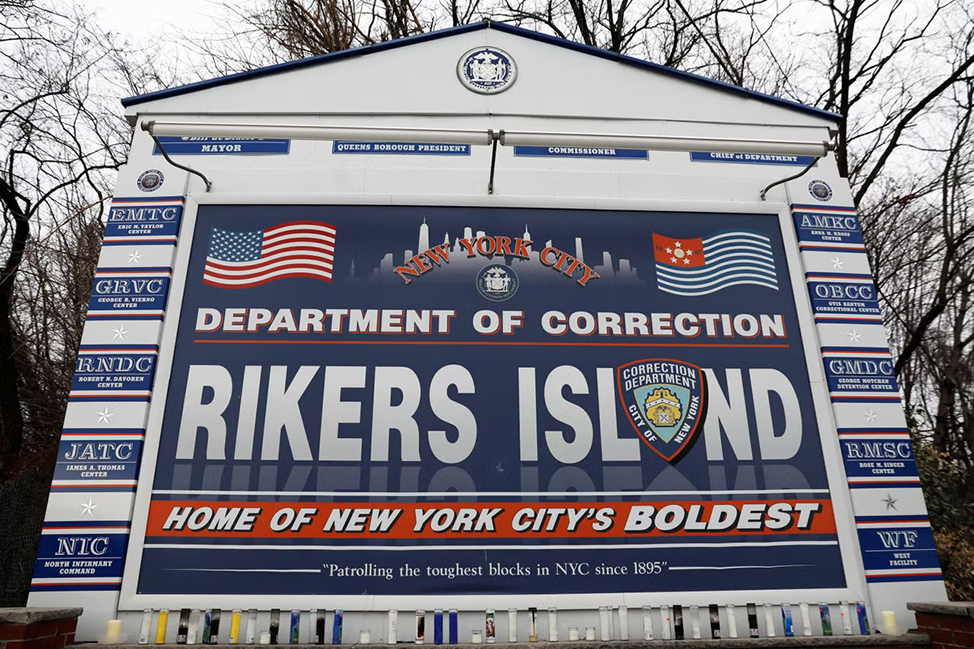

But it’s not easy to just start working in a prison. Thinking she was taking the best path, Joh initially volunteered to teach women in a low security facility, but as fate would have it, she was placed in men’s maximum security. “Riker Island is regarded as one of the toughest, most violent prisons in the United States,” says Joh. “It’s an old jail with several facilities, on an island in the New York Borough of Queens. It’s what is known in Australia as a remand centre, where people are held before their court case is heard. Most of those held on Rikers Island are people who cannot afford bail. So, they tend to be the poorest of the poor. The rest of the jail’s population are there because they’re too dangerous to be released or are regarded as a flight risk.

As Joh says, many of us don’t realise that we are in a prison of our own mind. We distract ourselves from repetitive, negative thinking by doing things like binge watching TV, excessive eating, drinking and shopping. We have the freedom to distract ourselves – and not necessarily with good habits. “We do all sorts of things to block out the feelings we have. People do, I did. Distraction is really just putting off or exacerbating the problem. That’s where meditation can be so useful, it relieves the negative thinking, creating a much quieter mind. If you’re not incarcerated, you also have the freedom to get help” says Joh.

“But incarcerated people not only have much more difficulty escaping negative feelings because of the limitations on how they can distract themselves, they also have very few options to find help. So, if I can provide meditation as a reprieve and an opportunity to actually discover the peace within them, then that's actually very exciting. Even imprisoned you can feel good because your inner life guides how you feel, much more so than the circumstances you are in. I want people to have that opportunity – that's kind of my mission.”

Joh says a disproportionate number of incarcerated people have experienced childhood trauma. And studies show childhood trauma has been linked to anti-social behaviour. She says meditation is one methodology that has been shown to relieve toxic stress which underpins these behaviours. There are studies showing incarcerated people who meditate are less likely to re-offend, she says.

Joh was just getting started at Rikers Island in February 2020 when COVID-19 hit with all jail access denied. During the shutdown she established The Light Inside, an organisation designed to attract funding for Joh and her like-minded colleagues to establish a Vedic Meditation (VM) program for prisoners and corrections officers alike across the US and Australia.

Vedic Meditation comes from Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, who famously taught the Beatles. The method is steeped in tradition and, before starting the first of four classes which makes up the VM course, everyone is given a flower. “I give all the men a yellow rose and I never really know if they will take it seriously, but they always love it, and ask ‘Miss, can I keep the rose?’ I tell them to put it next to their bed to remind them to meditate in the morning.”

Joh’s teaching at Rikers has now resumed and she also hopes to be working with women serving life sentences in a prison outside Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Meanwhile, The Light Inside is currently in talks with a Corrections Department in Australia about beginning a Vedic Meditation program in an Australian prison.

Today, Joh still makes trips to Australia to host retreats and visit her family, but remains based in the US with her wife, Susan, and dog, Tiny. “I'm in New York, I just love it so much. I just love the pace. I love the intensity.” Which is probably also why she ensures she takes time out each day for meditation.

You can find out more about Joh’s initiative at the-lightinside.com.

Meditation in the modern world

“I think that one of the tools that most people need for a modern workplace is meditation. Just exercising doesn't do it; it may burn off the adrenaline, but deep inner peace is where you find creativity and clarity.

If you’re young with a career and busy social life, there’s a ton of stress pouring into your body and there's no real outlet for it. There's no way to process it from your body – and it’s exhausting. Meditation releases stress from the body, allowing you greater creativity, clarity and the capacity to regenerate, to rejuvenate.

I constantly teach journalists who get to age 40 and they're exhausted, which I completely understand. But give your brain a rest for 20 minutes twice a day, and your capacity is just exponential.

Generally, men are more into the performance enhancement they get from meditation than women. Women will talk more about their emotions whereas for men it's another tool in their toolbox. As a broad generalisation, men use it more for performance, whereas women want to feel better; they want to feel happier.

The average age of people I teach would be 29. Younger people are less nervous about it. They are just way more comfortable talking about their emotions, they know that they need tools to look after their inner life. And increasingly they know meditation is one of those things.”

Joh Jarvis