22 December 2021

Kiera Sargeant

Bachelor of Nursing

When Kiera Sargeant was gifted a medical play kit as a child, she often spent her time checking dolls and their vital signs, imagining what it would be like to be a nurse helping those in need. Growing up in a very small town with a strong community spirit, Kiera’s compassionate nature was further nurtured with her family’s involvement in the Lions Club and other organisations, always helping her parents with different community activities.

These experiences were grounding ones and made her aware of ‘the bigger picture’. This was only compounded watching the news and becoming aware of conflict and natural disasters happening around the world. Kiera realised she had the ability to help and embarked on a path to become a nurse.

During her Bachelor of Nursing at UniSA, Kiera downloaded the application form for Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) and was sure this is where she wanted to take her career. Joining MSF in 2014 as the Deputy Head Nurse of a women and children’s hospital in South Sudan was a great learning experience and further reiterated to Kiera that this is what she wanted to dedicate her life to.

Since then she’s spent time in Nigeria and Iraq as a Medical Team Leader involved in different medical activities, sexual gender-based violence programmes, supporting women, men and children with medical and psychological support, and working in internally displaced people’s camps, providing primary healthcare.

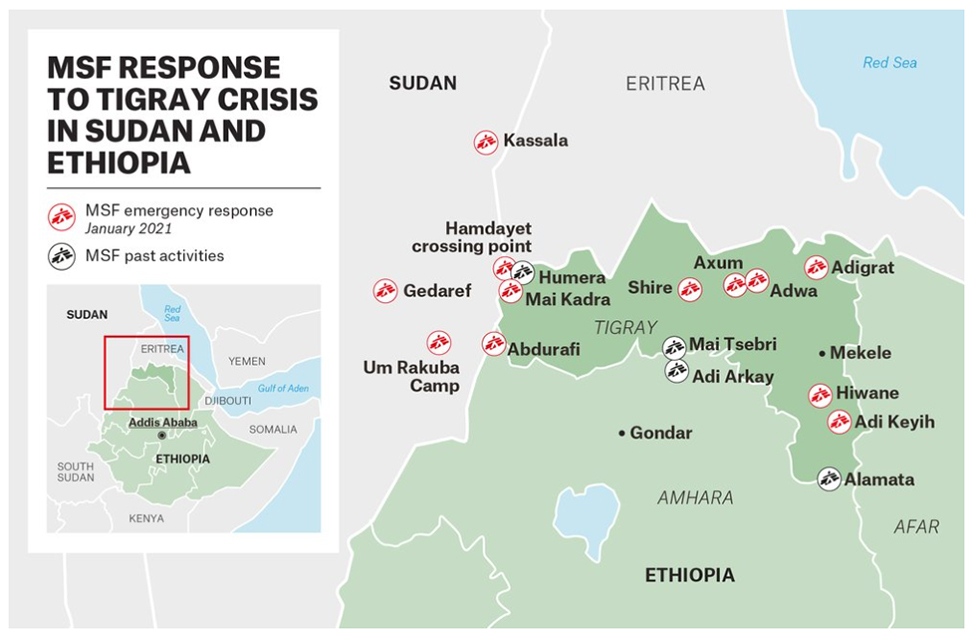

After leaving Iraq, Kiera joined the Emergency Team as a Medical Coordinator, where she spent time in Ethiopia responding to displacement and providing healthcare, water and sanitation to the population, then was stationed for two years in Syria, in several roles and medical programmes, before travelling to Sudan. Most recently, Kiera has been working as Medical Emergency Manager for the Emergency Support Department, supporting a team conducting an assessment in Latin America looking into vulnerable groups and neglected health areas, as well as research into the health effects that volcanic eruptions can have on people following the eruption in Goma, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Here, Kiera gives us a fascinating and inspiring insight into her life, work and travels with Médecins Sans Frontières, and her experiences that are at once devastating and hopeful.

You’ve recently spent time as a medical coordinator in Sudan. Could you tell us about this experience and what it was like driving MSF’s response to the refugee crisis?

At the end of November, we arrived in Um Rakuba Camp in Sudan’s Gaderaf State after dark and slept out in the open on some camp beds. The next morning at first light, we awoke to be surrounded by refugees asking what we were doing there.

The camp was completely unorganised with barely any shelter and only three large tents for a few thousand people. Other aid organisations were distributing food twice a day as a hot meal, but not what the Tigrayans liked to eat. There were a few latrines set up, but some had already become full. The first morning I spent conducting a rapid nutrition assessment – measuring children’s mid/upper arm circumference to determine whether they were malnourished or not.

We had basic medical supplies but were awaiting a shipment from the capital Khartoum to arrive and with one small clinic being run in another part of the camp a few kilometres from where we were, it was clear that the population needed access to healthcare, water and sanitation. We were able to build a rough shelter using local materials to act as a medical clinic and started to dig pits for latrines. Using the medical supplies out of the emergency rucksack, we started treating the most severe illnesses first.

After three days, the Head of Mission and myself, handed over the activities to the other MSF team, and joined our colleagues in Hamdayet as more and more people were crossing the river border. In Hamdayet we had set up a first response station at the riverbank, where we could assess the pregnant and lactating women and children aged six months to five years for malnutrition, as well as identify anyone who needed urgent medical attention.

The village itself had a small primary healthcare centre that was run by Sudan’s Ministry of Health. We collaborated with them to expand opening hours and activities to include free healthcare for the Tigrayans and Sudanese population hosting many of the refugees in their own homes.

We saw gunshot wounds, shrapnel wounds, as well as mental trauma and sexual gender-based violence cases, as well as other medical conditions and chronic health problems. Secondly, there was no access in the village to clean and safe drinking water, in collaboration with other organisations, we added two 5,000 litre water bladders to the clinic compound so that people could access water. We also built showers and latrines for people staying in the village.

The resilience of the Tigrayans was amazing to witness, they had fled their homes, often with nothing but the shirts on their backs, hiding in the bushes for several days trying to find a way to cross the border. There was a large number of medical professionals who had worked in the large hospital in Humera in Tigray as well. They all came to us in the first days to offer their support and willingness to treat patients and work with us.

In an emergency situation such as this, providing access to healthcare and the safe (chlorinated) quality and quantity of drinking water, as well as having latrines, are vital to the reduction of illness and the risk of diseases spreading. It also allows dignity to the population in need. It’s long days, often with little to no breaks, and it’s seven days a week.

We were lucky that a group of teachers had welcomed us into their home and provided us with a place to sleep. They were so accommodating and would prepare us coffee and beignets in the morning and a delicious meal in the evening, we slept outside under the stars as inside there was barely any room. We only had electricity in the evening, and there was no internet connection and rarely any data connection in the village.

It is a real privilege to be able to respond to these emergencies and support those in need, advocating to other organisations the needs and wishes of the Tigrayan population.

Could you describe a particular project or assignment that has stayed with you or had a big impact, either personally or professionally?

To be honest each assignment has stayed with me. The like-minded people that you meet and get to work with are hard to forget.

In South Darfur, Sudan, we were setting up an office and conducting assessments to start medical activities. Our plan was to go into the Jebel Marra Mountains to assess the health gaps as this area was rebel-controlled. It had been 15 years since there were health clinics there before the Darfur war.

We managed to negotiate access into the mountains, and having left the vehicle behind as there was no more tracks or roads, we loaded the gear we needed for three days onto our backs and walked into the rebel-controlled area. There we met with members of the community who had come down from the mountains with donkeys to guide us to their villages. We introduced ourselves, and then rode on into the mountains.

The landscape was absolutely stunning, though sadly along the way they pointed out buildings and structures that were once homes and health clinics destroyed during the conflict. We got to the first village just before sundown. The whole village had laid out welcome mats and were awaiting our arrival, the women were singing and dancing, and offering food and refreshments. We sat down and had a meeting with the village elders and then I was able to speak with the women to understand their concerns.

The next day we went to see potential locations for building a clinic that would be accessible to all the villages in the area. More meetings were held with different groups and we were able to piece together their stories and their concerns. One place we stopped for a break they showed us graves under a tree where the injured and sick die on their way down the mountain when trying to access healthcare. It can be up to a three-day journey to get to the nearest health clinic and hospital.

The last village we stopped at on our last day we started down the mountains to our pick-up point, the women were so excited to see us and be heard (we learnt later that we were the first foreigners they had seen in 15 years) they surrounded us as we rode the donkeys, singing and dancing, all in beautiful, coloured dresses for several kilometres. When we returned to the office, one of my tasks was to purchase three donkeys so that we had a mode of transport for going up into the mountains and hiring a ‘driver’ who would care for them and bring them to meet us when we were next going up.

It’s one of my favourite pieces of paperwork to date. The whole experience was so humbling, they were so welcoming and willing to share their concerns and hopes for the future. When we told them that we would build a clinic and start medical activities that would be free and accessible, they were so relieved. It makes me so happy to know that since I left Sudan, the clinic has been built and they have been providing healthcare to that population that was so vulnerable and neglected.

This kind of work can be quite intense – are there any moments of joy, hope or relief that you can recall? What would you say was the most challenging aspect of your work is?

One of the challenging aspects is leaving the projects – saying farewell to the team and leaving when you know there is still so much work and people that need help and support. Though at the same time it is good to recognise in yourself that you need a break and the fatigue that you have from working long hours, often without days off.

When on assignment, I often find it hard missing celebrations such as births and marriages of my friends and family. For example, one of my dearest friends gave birth on a day that I would consider one of my toughest whilst I was in Syria.

It can definitely be intense and sometimes scary, but there are many happy memories and hope. There are the medical saves where a child, a woman or a man come to you so sick and unwell, get better against the odds and make a full recovery. There are the celebrations with your team for treating the first 1,000 patients in a few weeks where you have a meal together, and then of course dancing!

In some of the locations I have worked, the team get together for a short coffee or tea break in the morning and it usually that involves some delicious food. Falafel, ‘cheesy bread’, fresh honey and yoghurt, it’s a time to take ten minutes with your colleagues and not talk about work, check in with them to see how their families are. It feels more like a family than just a team.

What would you say is your proudest achievement, and is there anything or anyone that you would say helped you reach your success?

One of my proudest achievements would have to be responding to the influx of displaced people to Al Hol camp in Syria in 2019. In the space of a few months the camp went from 10,000 to 75,000 people –often with 4,000 arrivals at one time that needed to be triaged and treated for health conditions before they were processed by camp administration and moved to a tent in the camp. Here we were able to build three primary health care clinics and one inpatient therapeutic treatment centre for malnutrition. We were also able to start water trucking and building latrines in a one-month period to help respond to the needs of the population.

In this time, I was able to work closely with our local colleagues and provide them with training and support to be able to respond. I am most proud of seeing how the team grew and learnt along the way – and when it came time for me to leave – how strong a unit they became with an increased knowledge of MSF and the values of impartiality, neutrality and independence which they were upholding under difficult circumstances.

As much as I was able to teach and impart knowledge to my colleagues, they also taught me a lot about their culture and their history. Without the local colleagues and other international staff that worked alongside me in the camp, and the team that managed logistics and supply, HR and finance, we would not have been able to respond the way we did, it really is a team effort.

One of my favourite memories is when I was having a conversation with my boss based in Amsterdam updating her on the situation. I was concerned about malnutrition in the camp and the fact that the children were separated from their families and sent out of the camp to the nearby hospital for treatment. She just told me: “Kiera, if you say we need a centre in the camp, just build it and start.” Having that faith and empowering me to do what was needed has stayed with me. It was built and then was expanded to go from 10 to 24 beds in the space of a couple of weeks.