28 February 2020

Professor Henning Bjornlund

Research Professor in Water Policy and Management

Bachelor of Business (Property)

Doctorate by Research, Business & Management

When UniSA’s Professor Henning Bjornlund first arrived at the Silalatshani irrigation scheme in southern Zimbabwe in 2013, he was confronted with contrast.

In one field an old woman was struggling to tend a maize crop overcome with weeds; too old to tackle the weeds, and too poor to afford fertilizer, she was ready to give up. In another field, a young farmer was organising a group of workers, growing garlic in what looked like a profitable enterprise.

Oddly enough, the scheme’s Irrigation Management Committee had asked the young farmer to cease planting, simply because garlic was not listed on the scheme’s 50-year-old cropping calendar of prescribed plantings.

Six years on, the garlic farmer has come to represent the remarkable improvement in the lives of farmers and their families in Mozambique, Tanzania and Zimbabwe thanks to UniSA research by international water policy and management expert Prof Bjornlund.

Switching focus from researching water solutions for the Murray Darling Basin to investigating viable water options in sub-Saharan Africa in 2013, he says the positive impact on lives in rural Africa has been deeply rewarding.

“Working in Africa is absolutely the highlight of my career,” Prof Bjornlund says.

“Certainly, I look to the irrigators in Australia and see that I’ve contributed to various developments and policy changes, but until now I haven’t been able to point to an individual family and say: ‘have a look at these people – they now have tin roofs. Or, look at this girl – she just finished university’

“Seeing how the irrigators have gained confidence, material wellbeing and capacity to educate their kids has been extraordinary.”

Prof Bjornlund has been working on a series of irrigation projects to alleviate poverty, improve food security, and provide economic growth and development for people in Mozambique, Tanzania and Zimbabwe.

Funded through the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR), in collaboration with CSIRO, ANU and undertaken in partnership with African researchers alongside small-holder irrigators and agencies, the projects have focused on improving farm productivity and profitability in tandem.

Until recently, irrigation in sub-Saharan Africa has been inadequate due to weak water governance, poor market integration, degradation and poor use of irrigated land.

A major challenge was shifting old habits entrenched since the first Zimbabwean irrigation schemes were built in the late 1960s.

“At that time, countries like Zimbabwe and Mozambique were able to secure donors to invest in these schemes so that they could produce staple food and counteract their concerns about food security.

“But over time, climate and weather patterns changed, and so too did productive crops, trapping many farmers in farming unprofitable staples.

“As staple food became cheaper to buy than to grow, farmers couldn’t productively maintain their crops, leaving them unwilling to maintain irrigation infrastructures until the structures simply deteriorated and collapsed.

“Today, the Director of the Irrigation Department in Harare no longer prescribes what farmers grow, so long as they make money and there is less conflict on the irrigation scheme. This is a direct outcome of research and education.”

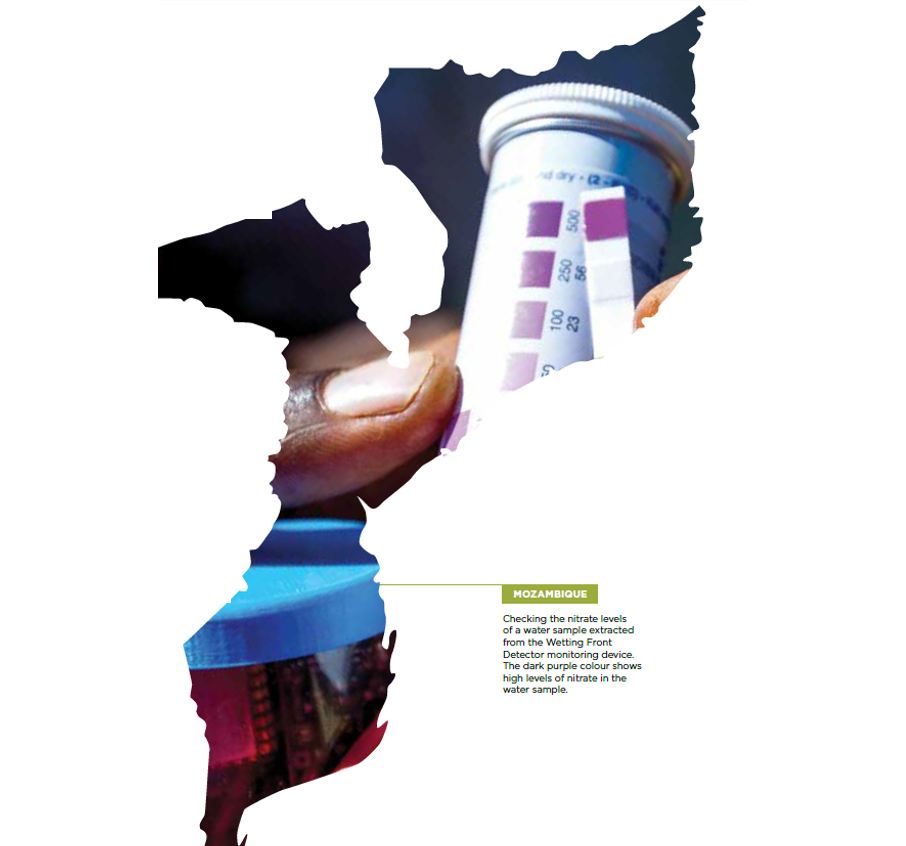

The first research project introduced on-farm soil moisture monitoring tools and Agricultural Innovation Platforms (AIPs) to five small-scale irrigation schemes in Mozambique, Tanzania and Zimbabwe.

UniSA researcher Karen Parry has been working on this project as part of her PhD. Recently returned from a three-month trip to Zimbabwe, she says the soil monitoring data is available to farmers.

“This data lets farmers ‘see’ the soil moisture status at three different depths and they record this in a field book alongside details about inputs, crop volumes, prices received, rainfall and irrigation events,” Parry says.

“The AIP process helps farmers overcome barriers such as access to markets, realising profit from improved yields, and building social capital, through problem solving and training. As a result, the project has created large-scale changes in behaviour and significant water savings in the small-scale irrigation schemes.

Parry says this has led to more water being available for downstream users, which in turn, has reduced conflict on the irrigation schemes and contributed to more people ensuring the maintenance of the system.

“We’ve also seen reduced labour requirements for irrigation, more opportunities for off-farm activities and income diversification, improved crop yields, better food security and more capacity to pay for health, education and irrigation charges,’’ she says.

“It’s been incredible to see the resourcefulness and motivation of the farmers as they quickly adapt their practices.”

This first irrigation project ran from 2013-2017; an expanded project is now halfway through a four-year period which finishes at the end of June 2021.

The ethos of the monitoring tools is providing an experiential learning opportunity – farmers learn on the job and the new knowledge spread saround the scheme.

Prof Bjornlund says the project has now been expanded across the three countries with farmers from the initial schemes helping to introduce the tools and set up AIPs in the new schemes.

"It’s becoming really powerful,’’ Prof Bjornlund says. “Farmers involved in a new scheme change their behaviours more quickly because there are other farmers showing them what to do.’’

Prof Bjornlund says while the use of the soil monitoring equipment has improved farm productivity – through for example, reduced water requirements and increased yields – it was important to introduce the tools and the AIP together to address poor market linkages and other challenges. In this way, farmers can achieve better returns and increased profitability from their crops.

“Until we start to think about irrigation schemes as complex socio-ecological systems, rather than concrete channels, diversion systems and pumps, we won’t change anything,’’ Prof Bjornlund says. “Building this understanding is basically the underlying philosophy of the project.’’

Prof Bjornlund says more productive harvests mean more money for farmers, enabling them to access additional land, farm inputs such as fertilizer, hired labour and equipment, as well as having enough money to send their children to school. It also lets them grow higher value crops, or use the increased income to buy staple food instead of producing it.

“We are very much looking at changing mindsets and encouraging behavioural change. Ultimately, the goal is to get farmers, and the institutions that surround them, thinking about how they can shift from subsistence growing to considering that they’re in business,’’ Prof Bjornlund says.

“Farmers now maintain field books and compute gross margins at the end of each season. They’re also starting to learn that other crops, like certain peas, beans and green maize have better gross margins.

“At our last meeting in Zimbabwe, farmers told us that the gross margin for garlic was up to 100 times more than grain maize. As soon as people can see that they can make money and save time, they adopt the new processes.”

He says time saving has been a major driver for change.

“Labour is one of the most constraining factors in the African farm household because most families can’t afford to pay for people to work, relying solely on their family labour.”

The benefits of lifting farm profitability through the new irrigation management practices have allowed families to diversify their income with some women able to use one day a week to bake buns to sell at the market or to open a hairdressing salon.

“This diversification is critical, as it introduces a secondary income should something happen to their primary crop,’’ Prof Bjornlund says.

Prof Bjornlund asked a Mozambique project partner why he was so engaged in a project that focused on farmer innovation and not water infrastructure, given that the partner’s in-kind contribution to the project was much higher than the research project funds.

Farmers are also using technology to link to buyers. Mobile phone use is common (network permitting) and farmers use the WhatsApp platform to connect to buyers and transporters, facilitating multiple small farmers to fill large orders, and get higher prices for their produce in markets outside the scheme.

Prof Bjornlund says the use of CSIRO-developed soil monitoring tools used in the research project are now being made in a South African production facility.

“By addressing water use productivity and profitability you start a self-reinforcing cycle of development,” Prof Bjornlund says. “I have seen middle-aged women stand out in the field saying, ‘we are now in business!’, and that’s because they’re starting to see something that’s profitable.”

Prof Bjornlund asked a Mozambique project partner why he was so engaged in a project that focused on farmer innovation and not water infrastructure, given that the partner’s in-kind contribution to the project was much higher than the research project funds.

“I can get untold millions to pour concrete, but I couldn’t get $50,000 to organise AIPs. Nobody wants to fund that kind of work,” the project partner said.

“Yet this approach engenders mindset change and leads to locally-driven solutions for the complex challenges bedeviling small-scale irrigation. “And, we’re changing people’s lives for the better.”

For more information, visit: unisabusinessschool.edu.au/magazine.