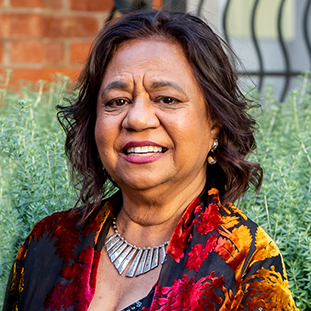

While she was still a teenager it was foretold that Henrietta Marrie would “travel over lots of waters”. While she did not think much of it at the time, this most certainly came to pass when she became the first Aboriginal Australian to be appointed to a United Nations agency. Based in Montreal, Henrietta travelled the world advocating for the interests of 1.2 billion people.

Information correct at the time of receiving the award

Henrietta Marrie (nee Fourmile) was born at Yarrabah, Queensland, an Aboriginal mission on the traditional lands of the Gunggandji and Yidinji peoples southeast of Cairns. She is the great-granddaughter of Ye-i-nie, a Yidinji leader whose leadership was formally recognised by the Queensland Government through the award of a king plate bearing the title Ye-i-nie, King of Cairns 1905.

Life for Henrietta and her five siblings changed when their father became a liaison officer with the Department of Aboriginal and Islander Affairs, a role that required the family to relocate every three years. With the family leaving Yarrabah for Palm Island and later Mareeba, Henrietta attended various schools – including a stint at boarding school in Townsville – before her qualifications at business college landed her a job in Canberra.

Returning to Queensland, Henrietta began a Diploma of Teaching, which she completed at the then South Australian College of Advanced Education. A Graduate Diploma of Arts in Indigenous Studies followed at what is now the University of South Australia.

“I found myself when I went to Adelaide,” says Henrietta. “I knew who I was … because the upbringing that I had was very similar to what I was learning.”

What she also found was the South Australian Museum’s collection of Aboriginal artifacts, including some from her homeland, which led to a lifetime’s dedication to cultural preservation. Henrietta became aware of the work of anthropologist Norman Tindale. When Tindale visited Adelaide in 1985, he met with Henrietta and showed her the Tindale Genealogies, the existence of which had until then been disputed. These records included around 50,000 Indigenous names and photographs, including one of Henrietta’s grandmother. The release of the documents, advocated by Henrietta, was a significant development that enabled many families to reconnect with their Indigenous heritage and land through native title processes.

Throughout this time, Henrietta was writing, publishing and presenting in the areas of intellectual and cultural property, Indigenous people working in museums, and Indigenous people and access to and benefit-sharing of genetic resources for agriculture and medicine.

Returning to Cairns and with further qualifications in environmental and local government law, she was able to question how the Crown could claim ownership of all that had once belonged to Australia’s First Nations Peoples.

In 1997, she became the first Aboriginal Australian to be appointed to a United Nations agency when she joined the United Nations Environment Program in Montreal at the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity.

Advocating for First Nations peoples and local communities across the Middle East, Africa, Asia, the Pacific and South America, many of Henrietta’s recommendations were accepted into UN guidelines to be promoted across the globe.

It was while giving a presentation on women in agriculture in Washington DC, alongside First Ladies including Hilary Clinton and Tipper Gore, and again at New York University, that Henrietta came to the attention of the philanthropic sector. Headhunted by The Christensen Fund, she relocated to split her time between Silicon Valley and Cairns. Over a period of nine years, she would oversee the distribution of $35 million to help promote, encourage and sustain Aboriginal biocultural diversity across Northern Australia.

Henrietta has also served as a Visiting Fellow at the United Nations University Institute of Advanced Studies in Tokyo and has been an Associate Professor at Central Queensland University’s Cairns campus. She continues to take on roles on advisory boards and in leadership positions, advocating for Indigenous communities and protecting their rights and interests, including the ARC Uniquely Australian Foods Training Centre at the University of Queensland, where she is an Honorary Professor.

In 2014, after compiling a report on racist behaviours against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander employees at the Cairns and Hinterland Hospital and Health Service (HHSs), she collaborated with her husband, Adrian Marrie, to develop a tool to identify, measure, and monitor institutional racism. Subsequently applied across Queensland’s HHSs, their work led to significant changes in the health system and drove legislative reform.

Her advocacy for ownership of Indigenous cultural property continues as she fights for the return of the shell regalia of Ye-i-nie, which she has only seen at an exhibition at the British Museum and again at the National Museum, Canberra.

In 2018, Henrietta received a Member of the Order of Australia and a mural dedicated to her was unveiled on the Cairns Corporate Tower. Bukal, a play taking its title from her traditional name of Bukal Bukal and based on her life and work, premiered the same year, and funding is currently being sought for a film.

She has been named one of the Queensland Greats and recognised with a Westpac – Australian Financial Review 100 Women of Influence Award for her work at the United Nations.