Article Lead In

07 July 2022

AUTHOR: WILL VENN

From fields to factories, to our own front doors: changes in the way we work are accelerating in the wake of the pandemic.

“9 to 5, yeah, they got you where they want you,

There's a better life, and you think about it, don't you?”

Dolly Parton’s 1980 hit song 9 to 5 captured it simply: the mundanity of prescribed office hours and daydreams of what an alternative could be.

But it would take a global pandemic to significantly shake up that nine-to-five cycle, bringing widespread flexibility to working arrangements, with thinking about that better life leading to the ‘Great Resignation’.

Over the first two years of the pandemic, $5.5 billion was saved in Australia in travel time costs alone as working from home became standard, a report by the iMOVE Cooperative Research Centre and involving UniSA, found.

The report, Prospects for Working from Home: Assessing the Evidence, found the proportion of people working from home increased from 8 per cent in pre-COVID 2019, to 40 per cent in 2020.

How fast the workplace is changing is evident not just visually in the many half-empty office spaces and decongested commuter routes in cities across the world, but also in matters of mental health, gender roles and applications of new technology.

Back in pre-industrialised agrarian society, work was physically demanding, governed by daylight hours and the seasons, and located largely on rural land with little requirement to travel far to work.

In the United States, the 9am-5pm, five-day working week emerged a century ago, when the Ford Model T motorcar rolled off production lines, assembled by a workforce engaged in eight-hour shifts. This established a production pattern that was adopted widely across manufacturing industries, and set a template for working life that has endured for decades.

More recently, the steady advance of service industries, the gig economy, dual income families, new technologies and automation has rendered this template less relevant in the 21st century and problematic by the time COVID-19 hit.

Director of the Australian Centre for Business Growth and ANZ Chair in Business Growth at UniSA, Professor Jana Matthews, describes the impact of the pandemic as akin to “pulling the handbrake on life”.

“Almost in an instant, remote work became a norm, flexibility was a baseline, and empathy became a foundation for how leaders treated their teams,” Prof Matthews says.

“The TV images and statistics of COVID patients around the world reminded us that ‘life is short’ and can end at any time.

“’Am I doing what I love and loving what I do?’ became a question many people began to think about quite seriously.

“Being required to work from home meant people spent less time commuting, and less expenditure on coffee, dining, petrol, parking and clothes.

“In short, the ‘hard break’ created time for many Australians to reassess their lives.”

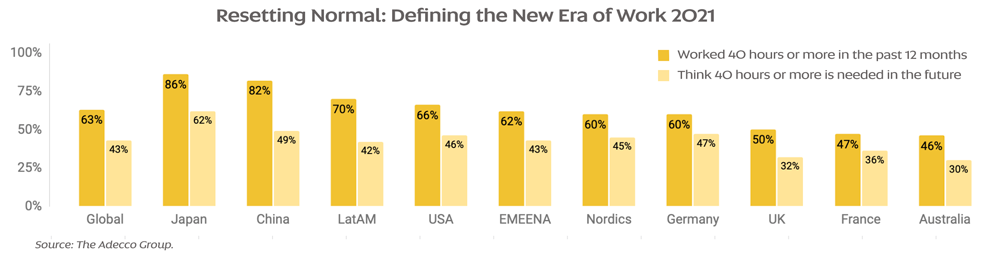

Research by international recruitment company The Adecco Group found that being able to maintain work-life balance is now of equal importance to receiving a good salary and priority in life “after COVID” when choosing a job.

In many countries, less than half the population thought more than 40 hours of work per week was needed after COVID.

The struggle to juggle

Maintaining a work-life balance is hardly a new idea though; the “struggle to juggle” is a maxim familiar to millions of working mothers.

The competing pressures on mothers who work full or part-time while also being primary carers for children at home is a concept that has been defined as “second shifting” by sociologist Arlie Hochschild who, since the 1980s, has described the state of play in the workplace as a “stalled revolution”.

UniSA Research Associate Dr Ashlee Borgkvist is examining flexible working arrangements, specifically identifying how fathers engage in flexible work.

“What we have discovered where there is stalling, is that there is still a real cultural barrier to fathers’ use of flexible work arrangements,” Dr Borgkvist says.

“The idea still persists that there are certain roles that mothers and fathers should play in families.

“The perception of the father being the breadwinner is still quite prominent within Australian culture, but even when mothers are the breadwinners, they are usually still held responsible for much of the care work and other unpaid labour at home.

“Removing that cultural barrier means providing more opportunity for mothers to participate in the workforce if they want to, but it also means sharing care work equally.

“We are also seeing more and more fathers expressing a desire to have greater involvement in care work but coming up against that cultural barrier.”

While sharing the care of children is one way to progress the revolution, much still rests on breaking stereotypes.

“This relates a lot to the way we construct masculinity and fathering,” Dr Borgkvist says.

“Participants in my research have expressed that they didn’t want to earn less than their wives or they didn’t want to be the ones at home taking care of their kids because ‘what would their friends think of that?’ Those barriers are still quite prominent.

“In Sweden or Denmark, there are family policies that have enabled different expectations of fathers to be fulfilled. For example, it’s considered odd if fathers don’t take time off after a baby is born in Sweden; that has become a cultural norm.

“In Australia, we currently have two weeks of government provided paid paternity leave – Dad and Partner Pay, which is paid at minimum wage.

“What we really need in Australia is a well remunerated, government-sanctioned paid parental leave policy that has a specified period for fathers, called a fathers’ quota. This is what is offered in Sweden – parental leave is shared but only the father can take the fathers’ quota – and if he doesn’t take it, the family loses it altogether.

“This is what creates more of a norm around fathers taking time off and that policy has led to cultural changes around father involvement in Sweden.”

Fewer than one in every 100 recipients of paid parental leave in Australia is male, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Family Database, whereas in Sweden fathers average around 30 per cent of all paid parental leave.

While policy change can aid cultural transformation in the workplace, culture can impact the way policy is deployed.

“One of the findings from my research was that within organisations there’s quite often a disconnect between formal policy and informal support for use of that policy,” Dr Borgkvist says.

“There might be a formal policy around flexibility that exists, but there might be an informal culture suggesting that men or fathers shouldn’t use that policy.”

The requirement to work from home because of COVID-19 lockdowns has not only created transparency around such policies, but embedded it in a way that suggests work-from-home practice will continue long after the pandemic fades.

“Recent research of employees from around Australia has found a majority wanted to continue the hybrid model of work from home and work from office, which I think is a testament to how influential COVID-19 has been in terms of making people more aware of flexible working arrangements within their organisations and how they can actually work,” Dr Borgkvist says.

“There was resistance before COVID-19 because many managers were still stuck in the mind frame of ‘If I can’t see my employees, how do I know if they are working?’, but the pandemic has shown they are still getting output from their employees.

“It has been beneficial to demonstrate that to managers as well.”

Not only beneficial, but for employees beleaguered by lockdown, it’s been empowering.

‘By 2030 people will be working 15 hours a week’

Associate Professor in Human Resource Management and the co-director of the Centre for Workplace Excellence, Connie Zheng, details the paradigm shift that is taking place in the employer-employee relationship.

“Organisations want to take back managerial control but have discovered that employees aren’t exactly ‘buying it’ anymore,” Assoc Prof Zheng says.

“Employees are asking: ‘why do I have to be back in the office when I’m delivering results, when I’m delivering the outcomes, when productivity has increased?’

“The focus is shifting from an organisation’s profits and performance outcomes to employee wellbeing and health benefits; from the employers’ rights to hire and fire to recognising their responsibilities to care and be fair to employees with reference to working conditions, especially related to the reduction of working hours and flexible work arrangements.”

Assoc Prof Zheng says there are examples of companies now using workplace flexibility as a key drawcard in their recruitment strategies and that to retain a productive and engaged workforce, offering flexibility is key.

“Discussions about flexible work arrangements as well as working fewer hours have been floated for decades,” she says.

“Economist John Maynard Keynes predicted that, as technology advances, humans should enjoy more leisure time. He suggested in 1930 that by 2030, people will be working just 15 hours a week.

“But the fast development of capitalism and neoliberalism – which enforces that we have to earn more, we have to compete and work harder, alongside the process of globalisation – has seen employee welfare became secondary to matters of organisational performance, output and productivity.

“But if you are looking at figures related to how many young people have mental health issues and how stressed out the workforce has become, you start to get a picture which demonstrates it’s not worthwhile to work more hours.

“People have become used to working 9am-5pm or more, five days a week, with previously little consideration from organisations that it may be possible to achieve the same outcome and productivity within fewer hours or within a more flexible time structure each week.”

In February this year, Belgium became the latest country to adopt a four-day working week. Employees are expected to work the same number of hours as previously, but they can choose to compress them into four days.

“Japan and other Asian countries have started the discussion about the idea of four-day work week; only a few companies have actually implemented the scheme in Japan and achieved success. But Iceland has already implemented it before Belgium,” Assoc Prof Zheng says.

While there is huge impetus for this change, Assoc Prof Zheng underlines the magnitude of the task and the potential outcomes associated with a workforce switching from five to four days.

“The discussion needs to be holistic and about how a change to a four-day working week can benefit employees and society,” she says.

“Health policies, welfare policies and industrial relations policies need consideration as well as political will for this to happen.

“Models of flexibility need to be considered as well as the different times and days that people work to avoid work teams becoming disjointed, depending on which days people work.

“A lot of concern about the proposed four-day week comes from organisations where tasks require a physical presence in the workplace, where work from home is not an option; think in terms of customer facing businesses such as restaurants or other service industries, which are required to be responsive to the needs of customers.

“Previously we defined classes according to income, we wouldn’t now want to create a division or conflict between those who have access to flexible work arrangements and those who do not.”

Assoc Prof Zheng’s observations are based on her expertise in looking into systematic human resources management at an organisational level. She says that company leaders must balance the factors that help employees achieve wellbeing and work life balance, against those required for an organisation to achieve its performance outcomes.

Whatever the future holds, an idealised vision of society, where work is optional and where material needs are met by a universal basic income, would still appear a way off and perhaps not as utopian as imagined.

Social philosopher André Gorz envisaged that when the production process demands less work, it becomes apparent that the right to an income can no longer be reserved for those who have a job.

Conversely the opportunity to engage in meaningful work and the association of work with self-value and identity is something that many would consider a basic human right.

To achieve that balance, enabling economic freedom from work with the right to work, requires solutions and flexibility that have yet to be fully realised, an evolution that will continue long after the clock ticks 5pm.

You can republish this article for free, online or in print, under a Creative Commons licence, provided you follow our guidelines.