Article Lead In

07 July 2022

AUTHOR: ADAM JOYCE

> BREAKOUT STORY: History is always out of date

Monuments are often seen as innocuous, but their prominence in Australian cities helps normalise the colonial past while making injustices harder to see.

In the time since 2020, the Black Lives Matter movement has prompted renewed calls for the removal of Australian monuments to colonisers, explorers and colonial administrators but almost all stand to this day.

While some argue the removal of statues erases or rewrites history, others say contested statues and monuments are themselves misleading. In Australia for example, many of the people immortalised as statues were involved in massacres, land theft and the oppression of Aboriginal people.

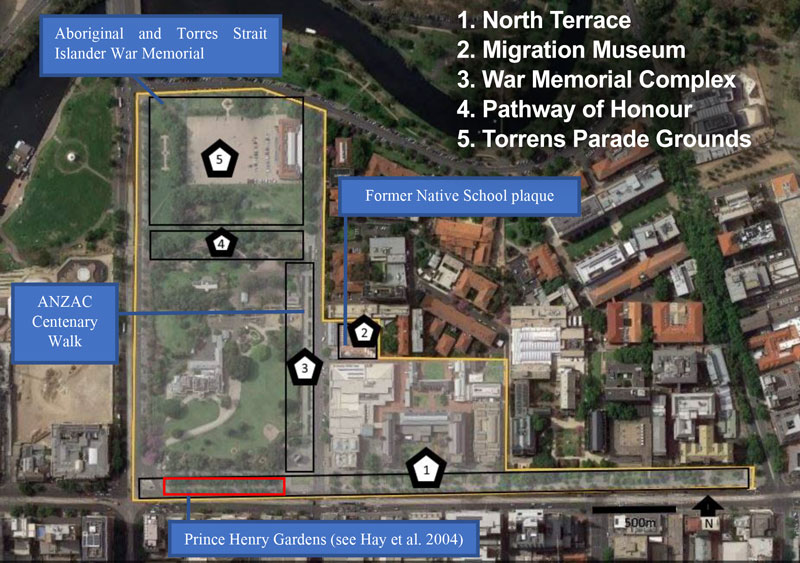

UniSA urban geographer Dr Matthew Rofe has undertaken a study of monuments in Adelaide’s cultural boulevard – North Terrace. It uncovered that the 256 statues, crosses, plaques and busts along the precinct (see aerial map below) tell a particular story.

Adelaide’s cultural heart

“Cast in stone and bronze, memorials speak to us of who we should admire, what characteristics we should aspire to emulate and why these people and their actions are worthy of admiration,” he says.

“Adelaide’s cultural precinct firmly remains a settler landscape … it’s a selective, authorised history.

“Heritage is basically authorised history that powerful people and groups find desirable for particular characteristics. In Australia, many of the monuments to explorers, settlers and colonial administrators are about this transplanting, this birth or growth of this European kind of ‘civilisation’, on this ‘wild, unkept frontier’.”

And while there was struggle and adversity, the monuments suggest so-called civilisation was achieved “nobly and peacefully”, ignoring the reality that colonisation in Australia was violent.

It’s now recognised that many statues perpetuate myths. For example, an inscription on the statue of James Cook in Sydney’s Hyde Park states that Cook “discovered this territory 1770”, suggesting Australia was unoccupied, denying 65,000 years of Aboriginal history.

Dr Rofe says by occupying civic space, monuments can help legitimise narratives of conquest and dispossession.

“People might say that a statue to Captain Cook is pretty innocuous, that it doesn't really matter,” Dr Rofe says.

“Well, it does, because these are physical manifestations of social injustice, of inequitable processes and structures that continue to empower and valorise the stories and identities of settler Australia, at the continued expense of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

“The process of colonisation was achieved through the dispossession of Aboriginal people from their land and the marginalisation of their identity, their history and their stories, so that the built landscape of post-colonial countries, particularly the cities, is European.”

Dr Rofe’s study of Adelaide’s cultural precinct, undertaken with Honours student Kate Croucher, found that monuments to Aboriginal people are exceedingly rare, with Aboriginal people represented in six out of 256 monuments (2.5 per cent).

Australian contemporary artist James Tylor has also researched Indigenous and European colonial history with a focus on South Australia, since completing his Masters in Visual Arts and Design at UniSA.

The Kaurna, Māori and European artist and researcher says most monuments of people represent a biased history, generally in favour of the person who’s been immortalised in stone.

“I think each monument has to be approached on a case-by-case basis, but when we’re talking about colonial statues, they tend to focus on one aspect of their lives – and that’s generally from a positive viewpoint,” Tylor says.

“History is a fluid thing, our ethics and morals change, so we need to view history through a contemporary perspective. We wouldn’t live in a less violent society if we didn’t make positive changes around negative behaviour from years past.”

UniSA Deputy Vice Chancellor: Research and Enterprise, Professor Marnie Hughes-Warrington AO, says the call for monuments to be removed is part of a wider movement, where people who had previously been ignored or silenced in history, are speaking up.

“They’re saying, we also have a view – that violence has been enacted against us, we don't get jobs at the same rate as everybody else; we are not in the high paying jobs, we're not on the boards, we're not in the corridors of power,” she says.

“History is part of that. If we're going to redress inequality and injustice, that's not using history politically, it’s just saying it's very hard to make a more inclusive world when the histories themselves are not inclusive.

“History needs to acknowledge dark moments too, including violence against Aboriginal people.

“When some people look at a statue, it might remind them that they're missing members of their family … so the stakes are not small and I think it's incumbent upon all of us to listen with respect.”

UniSA sociologist Dr Brad West says there has been a proliferation of statues in Western nations since World War I in what he describes as a ‘memory boon’.

“From the 1920s, there has been unprecedented levels of remembering and commemorating the past and part of that has been this kind of new ‘memorialisation craze’,” he says.

Another factor has been a tendency to commemorate relatively recent events, whereas in previous centuries, memorials were mostly created to the distant past.

“The main purpose of memorials is to be a site of ritual, symbolic remembrance practice,” Dr West says. “Monuments, memorials and statues only remain relevant if they’re a site of symbolic social action and gathering.

“Part of the rush to memorialisation is to do with the politics of recognition. We need to recognise difference. People need to be represented.”

When statues fall out of step with society

He says statues that have become the focus of protests by the Black Lives Matter movement, had largely lost their original power yet, at the same time, found themselves out of step with contemporary beliefs and attitudes.

“They have become a symbol of political movement around how the past is remembered, portrayed and engaged with,” Dr West says.

“One of the challenges with building monuments to people is that with cultural shifts, an individual’s politics, personal history and actions can become an issue.

“Every individual is complex and has multiple identities. There’s now a reluctance to overlook the problematic aspects of people.”

This is why many contemporary memorials focus on an event or use symbolic representation.

For example, the ANZAC Centenary Memorial Walk in Adelaide features images of South Australia's servicemen and women, and pavers embossed with the names of the places where they fought.

The memorial walk is one of two monuments built since Australia’s bicentenary in 1988 that commemorates the service of Aboriginal people; the other being the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander War Memorial in Torrens Parade Ground.

Dr Rofe says the Aboriginal war memorial is a beautiful and important monument but frames the contribution of Aboriginal people through service to Australia and the British Empire. It’s also located at the periphery of Adelaide’s cultural precinct.

“In no way do we wish to diminish the service of those individuals and their sacrifice but it's interesting that that acknowledgement only commences with service to Empire,” he says.

“There is no recognition that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people resisted colonisation, that they fought for Country, as opposed to defending the country of Australia.”

Only one monument in Adelaide’s cultural precinct acknowledges the adverse impacts of colonisation on Aboriginal people – a plaque outside the Migration Museum, recognising it as the site of the former Native School. It details how Aboriginal children were deliberately separated them from their families, beliefs and cultural heritage and trained to work for the colonists as artisans and domestic servants.

“That plaque is the only one that acknowledges that Kaurna people lived in that area and that colonisation had an adverse impact on them,” Dr Rofe says. “Unfortunately it's tucked away … and it’s made of plastic and is just weathering away.”

He says North Terrace is a “landscape of power”, however he doesn’t generally support the idea of tearing down problematic statues.

“There’s a flaw in the idea of tear it down, get rid of it – you haven’t done anything to remove inequality,” Dr Rofe says.

“You can relocate a memorial, do something to learn from it – erect counter-memorials, which speak to each other and are instructive.”

Tylor says there are alternatives to building statues. In many Aboriginal cultures, landforms often encapsulate an individual’s story, with the Mount Lofty Ranges embodying the creator ancestor of the Kaurna and Peramangk peoples (see breakout).

“From an Indigenous perspective, all of our histories are living histories, oral histories, so they're active within us, as opposed to needing to have something like a statue that is dead and dormant to memorialise it,” he says.

“Those oral histories have been handed down for many generations … we have the oldest recorded human history on the planet. Australian history should be respected and appreciated for that.”

He says the creation of monuments made of stone, concrete or metal involve environmental damage and that more environmentally friendly monuments should be considered, such as trees or indigenous plants.

He points to The Old Gum Tree (Kaurna name: Patha Yukuna) in Glenelg North, the site of South Australia’s proclamation, as an example.

“You don't need a monument to tell you about history,” he says. “I think people tend to think of statues in quite a rigid way yet with other structures such as building, they’re knocked down and replaced all the time – we can and should be much more fluid, they [problematic monuments] don’t have to stay.”

Colonial statues can be painful reminders of a one-sided history

Writing in the Adelaide Review, Jacinta Koolmatrie, an Adnyamathanha and Ngarrindjeri person working in the heritage sector, says First Nations people will never be able to heal from the trauma of Australia’s colonial past when it’s held up on a pedestal.

“Most statues in Australia are of White people, specifically White men who were considered significant in the creation of what we know as Australia,” she writes.

“For some this is a source of inspiration, but for those dispossessed and oppressed by the creation and continued existence of Australia, such figures represent the stealing of our land, the enslavement of our people, the control over our bodies and the erasure of our own histories.

“Many White Australians would not know who is memorialised around their city if they were covered up, and only really think about these statues when their removal is proposed. Such forgetfulness is not an option for First Nations and other people of colour, who are living with the legacies of these figures every day.

“I work in the city and am reminded of these histories when I pass them on every commute. I think about the pain that these individuals caused to our ancestors. I think of the removal of land, of the bloodshed. Simply to get to work. I block it out, because it is the only way I am able to function.”

In some instances, monuments are already being removed. Last year a towering statue of Captain Cook on a main street in Cairns was removed after the land it stood on was purchased by James Cook University.

Although some argue this is erasing history, many researchers say it’s actually a question of whose history is told.

Like Dr Rofe, Dr West says there are alternatives to removing monuments, such as using the sites for acknowledgement and debate over the complexities of histories.

“Monuments can be reframed, juxtaposed or set against other historical figures,” Dr West says. “For example, monuments on the battlefields at Gallipoli now incorporate Turkish perspectives.

“Traditional war memorials in Gallipoli were closed to former foes and did not resonate with young Australians.

“But since the 1990s and early 2000s, they now provide visitors with a different interpretive environment for those memorials to be seen and interpreted. It’s not always about replacing monuments, but providing new meanings.”

Dr Rofe says counter-memorials enable society to have “an open space for discussion – to engage people in respectful and open dialogue”. The next step in his project is to engage First Nations stakeholders about options to improve Adelaide’s cultural precinct to address who and what is and isn’t represented, empowering previously displaced voices. This will examine what form Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander memorials should take.

“Redressing historical silences is a cornerstone of reconciliation,” Dr Rofe says. “Australia’s only Aboriginal Governor, Sir Douglas Nicholls (who served as Governor of South Australia from December 1976), won two knighthoods, but there’s no memorial to him in South Australia.”

Turning history on its head … UnMonumental is a collaborative project by artists James Tylor and Matt Chun highlighting events from Australian history that many will be unaware of, accompanied by original drawings.

Turning history on its head … UnMonumental is a collaborative project by artists James Tylor and Matt Chun highlighting events from Australian history that many will be unaware of, accompanied by original drawings.Tylor is working on a project with fellow artist Matt Chun that turns history literally and figuratively on its head. UnMonumental is an Instagram art project sharing facts about Australia’s colonial and pre-settler past that few Australians are likely to know.

“I don't think most South Australians know the State's history,” he says. “UnMonumental is about presenting facts, histories that are not told in the mainstream.”

Tylor and artist Rebecca Selleck recently presented the installation Warpulayinthi (Colonial Slavery in South Australia) at the Art Gallery of South Australia, responding to the myth of South Australia’s “free state”.

“Much of South Australia was built on Aboriginal labour through indentured servitude, which would now be considered slavery,” he says. “It would have touched every Aboriginal family, mine included.

“It’s affected so many communities, so I wanted to say something about it.”

It’s only fitting that that the world’s oldest continuous living culture be given a say over what happens next on Adelaide’s so-called cultural boulevard.

Dr Brad West’s new book is Finding Gallipoli: Battlefield Remembrance and the Movement of Australian and Turkish History.

Dr Matthew Rofe’s paper, Memorial landscapes, recognition and marginalisation: a critical assessment of Adelaide’s ‘cultural heart’ will be published in an upcoming edition of Landscape Research.

History is always out of date

The idea of “rewriting history” is often used as a criticism, as if the past is being deceptively altered or erased. But rewriting history is exactly what historians do on a daily basis, as they re-evaluate the past and correct misunderstandings, as new evidence and perspectives are uncovered that change what we thought we knew.

UniSA sociologist Dr Brad West says the representation of the past changes over time.

“We see history through a contemporary lens,” he says. “We make sense of it that way.

UniSA Deputy Vice Chancellor: Research and Enterprise, Professor Marnie Hughes-Warrington, who’s a historian and philosopher, says there isn’t a singular, definitive history – and that’s a good thing.

“History is innately subjective because there's a selector who selects the evidence,” she says. “It is normal to select like a scientist. We interpret the evidence, we read the evidence, we take that evidence, and we make an argument from it. So it is a creation of the historian.”

Prof Hughes-Warrington says the fact people disagree about the writing and making of histories, with a diversity of views and opinions, is a good thing.

“That's not to say that the past didn't happen or that we can't be fair about the past – because we can all agree that something's happened,” she says.

“But is it the case that there's only one history on Earth? No, my office is full of them (history books) because they all reflect different bodies of evidence, different methodologies, and they reflect the argument of the person making it. And we expect that of history.

“Just imagine a world where you go into a bookshop, and there's only one history available. Would we be happy with that? I don't think we would.

“A healthy democracy encourages that difference of view.”

History comes in many forms.

“There's an ancient tradition of making histories in written form but there's also even more ancient histories that are expressed in stone, dance and oral form. There’s not a single, agreed definition of history and there hasn’t been throughout Earth’s history.

“Probably the only thing that you have in common about history globally is that it's made by a human. And there is no human on Earth that doesn't become part of that story.”

Current concerns about “rewriting history” are part of a long tradition.

“If you look at ancient history, you see people pulling statues down, overwriting inscriptions, destroying them, and engaging with the past in ways that indicate the person being memorialised is egregious to that group,” she says.

“So what we're seeing recently is part of a very long tradition of revising history, of changing it, of updating it – and in some cases, obliterating it.

“People have always made histories, they sang songs, recited poems … but social media and global communication make it possible for us to know what's going on over the other side of the world, really quickly.”

Prof Hughes-Warrington is involved in a project to capture history written from the perspective of the losing side. In partnership with Professor Daniel Woolf from Queen’s University in Canada, History from loss involves 30 historians from across the world.

“We’re looking at everything – from archives that were buried in the ground, literally buried in the ground in ghettos during the Holocaust, through to Confederate folk who were quite angry they lost and had clearly very racist views,” Prof Hughes-Warrington says.

“What's been the real privilege of that project is to discover that a ‘winning history’ and a ‘losing history’ are not diametrically opposed.

“In the making of history, people will use different forms of history in order to protect a story and to ensure its survival. Everyone talks about history written from the winning side … but some of our most poignant, incredible histories have been written from people that that were executed, that knew that they were going to die.”

History from loss will be published in 2023.

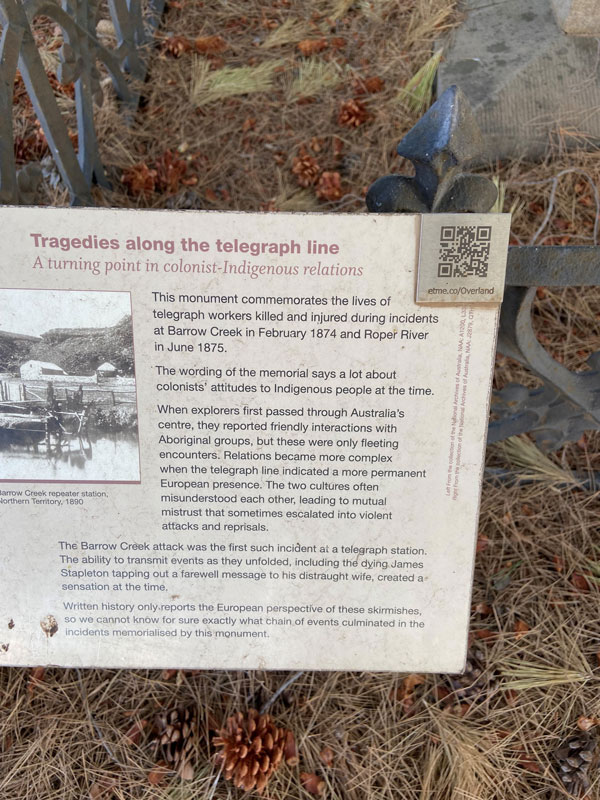

The Explorer’s Monument in Fremantle was erected in 1913 to honour Frederick Panter, James Harding and William Goldwyer, who were killed by Aboriginal people in 1864 while searching for new grazing land in the Kimberley region of Western Australia. In response, a reprisal party of colonists massacred up to 20 Aboriginal people. Aboriginal communities have long held that the Explorer's Monument was a racist work that presented a biased interpretation of the events at La Grange. In 1994, a plaque was added to the monument to commemorate the Aboriginal people who died as a result of frontier violence, creating a counter-memorial.

Aboriginal memorial in the landscape

The Kaurna and Peramangk people know the Mount Lofty Ranges as Yuridla. Yuridla (also Yurrebilla, Uraidla) was the body parts of the creator ancestor Nganu of the Kaurna and Peramangk peoples. His fallen body forms the Mount Lofty Ranges, with his ears being the twin peaks of Mount Lofty and Mount Bonython. Today, the spirit of Yuridla looks down from the hills and protects all forms of life along the plains.

What’s now the town of Piccadilly was his eyebrows. Piccadilly is derived from the Kaurna word, Pikudla, “the locality of the eyebrow”. Uraidla is a European corruption of the word Yuridla, which means “two ears”.

You can republish this article for free, online or in print, under a Creative Commons licence, provided you follow our guidelines.