25 June 2021

AUTHOR: DAN LANDER

> BREAKOUT STORY: Big picture research

Sometimes it feels like placing a value on research outcomes can be more complicated than the research itself.

For much of the past decade, Australia has invested a little over $30 billion annually into research and development, with the nation’s universities responsible for about one-third of that activity.

In the past 18 months, of course, the research world, like the rest of the planet, has been turned upside down by COVID-19, and it is unclear what those same numbers might look like in coming years. What is clear, however, is that thanks to this unprecedented disruption, now, perhaps more than ever, research is being asked to ‘prove its value’.

While the current scenario may have brought the issue into sharper focus, discussions about how we ‘value’ research are hardly new, and it is broadly understood to be a question with many answers.

From the revenue generated by commercialisation; to the educational uplift of new knowledge; to the social impact of finding novel solutions to our collective challenges – it is difficult to suggest one value of research is more important than any other. In fact, according to UniSA’s Deputy Vice Chancellor: Research and Enterprise, Professor Marnie Hughes-Warrington, the truest value of research may lie in the push-and-pull of those many dimensions.

“When we consider what makes the world a better place, the important thing to remember is people don’t live their lives in separate buckets,” Prof Hughes-Warrington says.

“Most people understand that life is a kind of integrated range of health, economic, social, and emotional forms of prosperity – it’s not just physical prosperity, but also wellbeing and happiness. So, when we're looking at how research leads to a better society in terms of the financial outcomes, wellbeing outcomes and societal outcomes, you can't split those things apart.”

Despite this multifaceted value, recent years have seen growing emphasis placed on the tangible, quantifiable outcomes of research, particularly the commercialisation of research outcomes. The wide-ranging impacts of COVID-19 have reinforced that view in many sectors.

In February, federal Education Minister Alan Tudge released a statement setting out a clear agenda for what the Federal Government wants, possibly even expects, from the nation’s research community.

“We want academics to become entrepreneurs, taking their ideas from the lab to the market,” Tudge said. “We want them to be properly rewarded for their breakthroughs and their engagement with business … we know that more innovation activity will lift our nation’s productivity.”

While most people in the sector are wary of yoking all research to commercialisation, a statement from the Australian Technology Network of Universities (ATN), which includes UniSA, acknowledged “Minister Tudge’s vision for the future of the higher education and research sector is an endorsement of the way ATN universities work”.

Partnered research, focused on specific, tangible outcomes has long been the core mission of UniSA academics across a wide range of disciplines, and Prof Hughes-Warrington says UniSA is well positioned to prosper in the current research climate.

“We are so good at this already,” Prof Hughes-Warrington says. “According to the 2020 THE World University Rankings, we're number one in Australia for industry partnered research and that's not surprising, because it's just been a critical part of our DNA at UniSA for a long time.

“We never ask research questions in an empty room. We've always asked those questions with community and business. That wall between us and the community doesn't exist – we lowered that one 30 years ago and said, ‘We're in the room with other people, we need to understand how we can work together to solve these problems’.”

Fit for purpose

Asking questions lies at the heart of research, and in many ways, the quality of the research depends on the questions you ask. By working with partners who have specific problems to solve, researchers gain a better perspective on the kinds of questions they need to ask.

“Many of the problems that UniSA works on come from partners saying, ‘Could we do this better?’,” Prof Hughes-Warrington says. “Then we do the hard work of figuring out how to say yes to that, figuring out the questions we need to ask to solve the problem.”

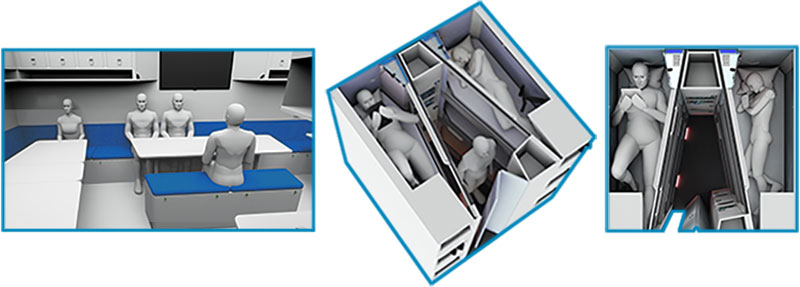

A great example of the challenges associated with simply figuring out ‘what the question is’ can be found in the work of a team led by Dr Peter Schumacher. Dr Schumacher is chief investigator on a project with the Defence Science and Technology Group (DST), developing human-centred design methods to improve life aboard Australia's future submarines.

“This has been an interesting collaboration, because when they first came to us, it wasn’t even just that they were looking for answers, they really didn’t even know what the questions were, nor the best methods to tackle the problem,” Dr Schumacher says.

Posed with the challenge of designing a submarine that provided a better experience for those onboard, Dr Schumacher’s team really was in uncharted waters.

“No one had tried to implement a human-centred approach in submarine design in this way before,” Dr Schumacher says. “Shipbuilding, in general, is only just catching up to the idea of human-centred design, even though that idea has been used in a range of industries such as aerospace for a long time, which genuinely surprised me.

“Now, the navy has become increasingly aware that the nature of work is different than it was in the past. Much of the job now is very technical, with more interfacing with technology and higher order thinking than in the past – it’s more brain than brawn. This means you’re competing for a different type of talent, and if you’re competing, then you need something to offer – a better working environment is central to that.”

Demonstrating the many dimensions of ‘value’ in partnered, industry facing research, Dr Schumacher’s team is not only improving life for Australia’s submariners and boosting the value of the navy’s core business, it is developing innovations that could influence the whole future of shipbuilding.

“Our philosophy is, ‘Do the right thing, and do the thing right’,” Dr Schumacher says. “And with many of the improvements we’re making, it’s often a case of, ‘Don’t create bad situations just because of clumsy oversights, where a bit more care and thought can make large improvements’. It’s really as simple as, ‘Don’t do dumb stuff’, but in the past, no one has been paying enough attention to identify and suggest the necessary interventions based on human factors.”

Discovering that ‘dumb stuff’, says Dr Schumacher, required a very different approach than that previously taken to submarine design, asking different questions of different people.

“Rather than focus on quantitative, technical aspects of design, we spend a lot of time talking to submariners,” he says. “And much of that’s very open ended – for example, we can have a two-day workshop where the first question is a broad as ‘So, submarines, what’s up with that?’ The aim is to understand the widest context before delving into the nitty gritty details of the strange working life of a submariner.”

Following from that, the key research challenge for Dr Schumacher’s team is to translate insights from submariners into innovations naval architects can incorporate in future submarines. And the best way to achieve that is to design and build prototypes of their ideas.

“Our task is to assist DST to establish design benchmarks to assure the quality of future submarines,” Dr Schumacher says. “We learn by creating designs, and doing this takes ergonomic concepts from the abstract to the concrete.

“We need to shape the engineering space and address human factors early in the process or it is too late – changes are hard to make once built and these submarines will be around for a generation.

“But if you ask the right questions and you make the early interventions, then it’s just a smarter way of arranging what you’ve already got by being more alert to the human implications. It won’t necessarily be harder or cost more to build, it will just be better connected to actual user experiences.”

Using science to solve real world problems

As is the case with Dr Schumacher and his team, collaboration can often lend a much-needed focus to research. In another sense, however, collaboration can also be the pathway to research diversity, revealing new dimensions to existing expertise.

Professor Sanjay Garg is Director of the Centre for Cancer Diagnostics and Therapeutics (CCDT) and Pharmaceutical Innovatvion and Development Group (PIDG), and his cross disciplinary team works across a staggering range of research areas, including using 3D printing for targeting of anticancer drugs, solutions to antimicrobial resistance, and treatment of stomach ulcers in horses. The diversity, says Prof Garg, comes from a willingness to collaborate.

“The best part of my job is talking to clinicians from hospitals and asking them, ‘Is there any unmet clinical need that we can solve with good science?’ It’s not easy, but if you keep asking the right questions, you find the problems that need solving,” Prof Garg says.

“At the time I did my PhD, HIV was a very serious issue, just as coronavirus is now, and I was trained to do something to stop HIV from spreading, and that ingrained in me that whatever we do has to be meaningful, has to be useful to society at large.”

From Prof Garg’s perspective, the easiest way to ensure research is meaningful – or has ‘value’ – is to engage with the end users or people who are likely to benefit from it. Key to this, he says, is recognising there are usually multiple stakeholders who stand to gain from a successful project.

“While you can research anything, I have always focused on research to solve specific problems,” Prof Garg says. “About three-quarters of my research funding comes from industry, and when industry gives you money, they do so to make money, but at the same time, the research is always aimed at solving a specific, real world problem.

“Because of these relationships with industry, our research becomes very focused on patient needs – our partners know the unsolved problems, and they come to us to help solve them, which means we benefit both industry and patients.”

Prof Garg also emphasises the value collaborative research holds for education, with his students benefiting from direct contact with both the patients they are being trained to help and the industry channels they will ultimately be working in.

“As part of their training, my pharmacy students, who are a major part of my research team, have to go and work directly with patients. So, I can integrate students’ training needs with industry requirements, leading onto ultimately solving a genuine problem. Students find this really engaging as well, and that makes it exciting for me to teach.”

This synergy in Prof Garg’s work, between opportunities for the researcher, the insights of the partner and the multiple benefits to society – health, wellbeing, education – is a powerful demonstration of the value of research. It also highlights how difficult it is, even with specifically industry-focused research, to pinpoint any one metric for judging that value.

“Look around the world,” Prof Hughes-Warrington says, “and ask whether you are completely happy with the way everything is, or whether you want it to be different and better. If you think the latter, then research is a critical part of achieving that, but how you measure ‘better’ is complicated and multidimensional.

“Even so, I always say to people I am in charge of the portfolio of adventurers and dream makers, because the people that we have in our research community are driven by a fundamental desire to make things better.”

Big picture research

UniSA leads the nation in industry engagement, ranking number one in Australia for industry research income in the 2021 THE World University Rankings. Building on this, this year will see the launch of the University’s new Enterprise Hub, an online portal and physical shopfront for industry, government, community and not-for-profit engagement with UniSA.

The hub will bring together a number of UniSA concentrations, with the Innovation & Collaboration Centre (ICC), Executive Education, Research and Innovation Services (RIS) and UniSA Ventures all set to relocate to the hub.

UniSA’s Deputy Vice Chancellor: Research and Enterprise Professor Marnie Hughes-Warrington says the hub will expand and strengthen the University’s connection to the community, and give industry partners better access to the full spectrum of UniSA’s expertise.

“We are working to accelerate enterprise in South Australia – a state that is already kicking innovation goals – through our new Enterprise Hub,” Prof Hughes-Warrington says. “This is an outside in, one stop-shop for creating and sustaining partnerships.

“Partnerships are dynamic and powerful, and while an industry partnership might start with one part of a university or be anchored there, it rarely stays there. Most importantly, partnerships cross education and research.”

This ‘open door’ approach to research and education is also reflected in UniSA’s project-based PhD, which partners prospective research students with structured projects designed to deliver real world outcomes in conjunction with industry and community.

“This is fundamentally about hospitality and generosity, which are the engines of universities,” Prof Hughes-Warrington says. “You've got two choices when you know somebody's coming to your door – you can sit and wait for them or you can go out and greet them. The project-based PhD is going out and greeting people.

“So rather than waiting for PhD students to come to us suggesting projects and us figuring out slowly how to enrol them, what we're doing is going out and saying, ‘Here are projects that we have, here's who we partner with in these projects,’ and seeking talented PhD students for those projects.”

As part of developing the project-based PhD, Prof Hughes-Warrington says UniSA has tracked more than three million job ads in Australia to determine career path options for PhD graduates, with the results showing there is demand for research intensive graduates in industry, not just academia.

“Interestingly enough, it's not just the technical capability that employers are seeking, they're actually looking for the skills of a really good academic – teamwork, great communication, creativity, curiosity, ability to solve problems, think about risks,” Prof Hughes-Warrington says.

“All of the skills and hallmarks of a great researcher are exactly the skills industry is looking for, and we want to communicate that more effectively to industry, to support our PhD students and say ‘these are the things they can do, these are the capabilities that they have’.”

You can republish this article for free, online or in print, under a Creative Commons licence, provided you follow our guidelines.