Article Lead In

22 November 2021

AUTHOR: ADAM JOYCE

The idea of researchers working in silos is increasingly a thing of the past. The health issues facing society cannot be solved in isolation, requiring expertise from a range of areas including science, technology and the creative industries.

Health researchers have always had to call on the expertise of those outside their area.

UniSA research fellow Dr Ian Johnson says that to find biomarkers for cancer you need a multidisciplinary team including data scientists to analyse gene expression changes, image scientists to support digital pathology and chemists to create a new compound.

“And if you want to image cells you need new microscopes and new ways of visualising even smaller things inside the cell at super resolution, which means you need physicists.

“All these plug in and give you new answers to things that as a cell biologist, I wouldn't even have thought possible.”

The cancer biologist wants to take his research to the next level – space.

Without gravity, diseases develop differently, providing opportunities to pinpoint cellular changes and identify new treatments.

“Zero gravity is such a different environment to expose cells and organisms to and they react very differently,” the aspiring space biologist says. “You can observe new pathways and processes in these cells, which you can then target to try and prevent the disease from occurring.”

You don’t have to go into space to simulate a zero gravity environment. There’s a small benchtop apparatus called a random positioning machine.

“The machine turns in such a way that the cells that are growing in there don’t know which way is up. And that really is what microgravity is – it's constant freefall. And so by constantly turning the sample, it’s always falling.”

But random positioning machines are prohibitively expensive.

“The good news is that at the uni there are other scientists interested in space biology,” Dr Johnson says.

He’s working with Future Industries Institute research fellows Dr Xanthe Strudwick, who specialises in wound repair, and Dr Giles Kirby, who has founded a startup called Firefly Biotech to develop a more affordable microgravity simulator.

“You really need engineers, such as Giles who has expertise in plasma coatings and modifying substrates to generate new types of consumable,” Dr Johnson says.

But sometimes the solution to a health issue comes out of left field.

UniSA Professor of Sensor Systems Javaan Chahl started in computer engineering before pursuing a PhD in neuroscience and robotics in a biology faculty, a combination which has given him a unique perspective on the world.

“Biologists think very differently to engineers. Engineers tend to focus on what they’re trying to make, and look for supporting arguments to make something … whereas biologists tend to be much more research question driven – so what’s going on in this system? How do we expose this system? Usually with a lot of difficulty. Because insects and rats don’t talk, you have to expose their processing through their behaviour or very difficult measurements of the electrical signals in their brain.”

The genesis of a drone that can find people with COVID-19 symptoms

Prof Chahl ended up specialising in insect neurophysiology, including looking at honeybees, spiders and dragonflies. His engineering background meant he was able to interpret parts of invertebrates operating as a machine.

By researching how insects fly, he got involved in developing unmanned aerial vehicles, better known as drones, to test algorithms associated with insects. He became the Defence Department’s primary technology expert on integrated systems such as drones, before they were common.

This experience and knowledge, spanning neuroscience, biology, engineering, systems and robots means that unlike many researchers, he sees them all as interrelated.

“But people like me do require ultra-specialists who can focus on small points rather than broad areas,” he says.

“Interdisciplinary respect is absolutely critical. It’s really dangerous to be dismissive of other people’s expertise.”

This approach led to Prof Chahl tackling a number of health problems through his work – the best known being a drone that can detect people with infectious respiratory systems, dubbed a pandemic drone, and which has been commercialised by a North American company.

“Prior to the pandemic drone we were already interested in the use of cameras for measuring the vital signs of adults and children,” Prof Chahl says.

“Defence does a lot of relief missions and it occurred to me it would be very useful to know what state people were in if you’re trying to render them aid.”

Prof Chahl worked with UniSA neonatal critical care specialist Kim Gibson on a computer vision system that can automatically detect a tiny baby’s face in a hospital bed and remotely monitor its vital signs from a digital camera with the same accuracy as an electrocardiogram machine. The research led to a partnership with Flinders Medical Centre in Adelaide, allowing Prof Chahl and Kim Gibson to monitor heart and respiratory rates of infants in Flinders’ Neonatal Intensive Care Unit using a digital camera.

Prof Chahl also worked with colleagues at Middle Technical University in Baghdad to develop a low power fall detector that could dispatch a drone to help.

The study was based from various Iraqi hospitals including in Erbil and Mosul, where roads were often blocked, delaying ambulances. Drones were able to reduce response times to fall victims by up to half and deliver medical services.

His exposure to diverse fields during his PhD, from zoology, biology, psychology and neuroscience to defence and plant science, means that sometimes collaboration for him involves “a dialogue in my head”.

“I don’t see a boundary between all of these things and engineering,” Prof Chahl says.

There are many ways to bring people from different specialities together to tackle complex health problems.

UniSA lecturer in architecture and co-design expert Dr Aaron Davis says the focus has shifted from undertaking health research on people, to undertaking research with people.

UniSA has a Design Clinic which brings together researchers, students and industry to focus on effective co-design in healthcare.

“The real impact in what we're doing is the ability to bring together those complex teams that can solve problems that no discipline can on their own,” Dr Davis says.

The UniSA team worked with clinicians to get insights into the problems they were trying to address as well as with representatives of people newly diagnosed with type 2 diabetes.The Design Clinic uses a process helping people from diverse backgrounds to work comfortably together. The clinic is currently working with the CSIRO on a project to better support people who are newly diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. They wanted a way to empower people with diabetes to proactively manage their health as well as improving access to information and advice.

A digital health solution in the form of an app was the result.

“It really leverages available digital technologies as well as health knowledge and design knowledge to create something that is less resource intensive but delivers a higher quality and standard of care to people with diabetes,” Dr Davis says.

The Design Clinic Is led by Research Professor for Design Ian Gwilt.

“The first part of the process was to invite people with lived experience of being recently diagnosed with type 2 diabetes to share their own thoughts and insights and desires and needs around what would be useful to them,” Prof Gwilt says. “And what came out of that process is the need for a tool that helps people come to terms with being diagnosed with type 2 diabetes and to begin to change their behaviours.”

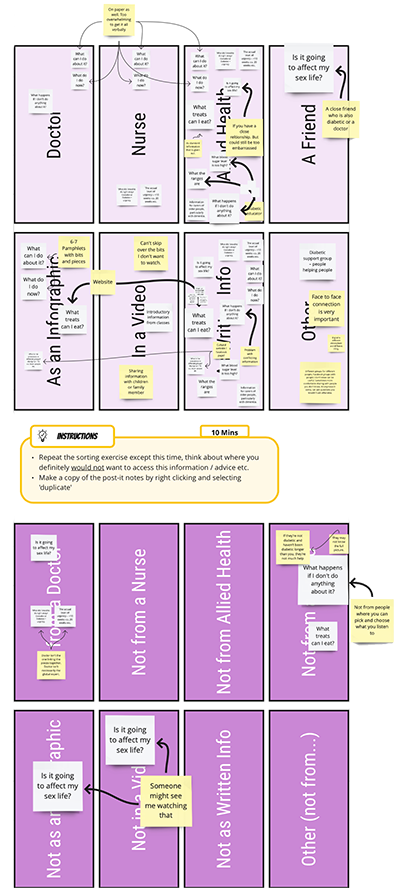

Example of an online whiteboard for visual collaboration.

Example of an online whiteboard for visual collaboration.Prof Gwilt says that for the research process to work successfully, participants need to be able to engage “in their own time, in their own spaces” – workshops shouldn’t be the default. The Design Clinic allows participants to use a range of online forums, interactive booklets and digital post-it notes to provide input. The app will allow users to document and record their own journey and their health stats, and provide corresponding information and advice, checked by health professionals.

It’s the idea of the public being co-researchers and active participants rather than “passive sources of data”.

“You can look at data and see what’s happened but by engaging with people we can understand why something is happening and this allows you to look at both aspects together to give you a better picture of what you’re trying to solve,” Prof Gwilt says.

“Doing it this way is time consuming, it’s more expensive, but the upshot is you end up with more effective solutions.”

The Design Clinic approach was pioneered by Match Studio, which provides opportunities for students to work with industry and government to solve complex challenges, which often span a range of disciplines.

Bringing people along for the journey

Match Studio director Dr Jane Andrew says the key is involving design professionals at the beginning of any project rather than the creative industries being seen “as an aesthetic afterthought”.

“The key to user centred design is understanding what the challenges are before you leap in and decide what the tool or vehicle is to address that challenge and to recognise that sometimes you can't completely solve a problem,” Dr Andrew says.

“Designers often fall into the trap of developing solutions for people without the people who’ll need to use that thing in the room. It’s very important for us to bring in people who are likely to use the design into the really early stages of understanding what the challenges are.”

Psychologist Dr Gareth Furber contacted Match Studio to discuss how psychologists could collaborate with emerging designers to create engaging and informative mental health education materials for the public. The result was an annual studio project and exhibition, Visualising Mental Health, in which UniSA Communication Design students develop clinical tools and product prototypes in consultation with practising psychologists.

One of those challenges was to improve mental wellbeing for new mothers.

“This group of young design students recognised that when new mothers come out of hospital, everything's focused on the baby,” Dr Andrew says. “You get a blue book when you leave hospital in which you record the baby's measurement and other data but there’s very little about the mother so they came up with the idea of a new booklet called Mother in the Making – a reflection booklet designed specifically for them.”

A prototype of the booklet will be piloted in a number of hospitals.

“We'll be working with [Associate Professor of Midwifery] Lois McKellar to get feedback from mothers and to do some survey work,” Dr Andrew says.

“We think about projects not just as an isolated challenge but get our students to ask what context does this challenge sit within.

“It's about giving everybody a voice. The tools and techniques that we use strive to create a level playing field for people from different disciplines and to stop us making assumptions based on professional, cultural and personal biases.”

Dr Andrew says innovation begins and ends with education.

“You can't expect to create change unless you nurture people who are passionate and want to work in this way,” she says. “If we want to change society or make things better and enable changes in the workforce and support innovation, we have to make sure the next generation of professionals, our students, have the tools to do it. Some people talk about them as soft skills but this is not soft, it’s hard – it’s critical.”

Tech solutions to health issues

The pandemic drone

UniSA researchers have designed world-first technology that combines engineering, drones, cameras, and artificial intelligence to monitor people’s vital health signs remotely.

In 2020 UniSA joined forces with the world’s oldest commercial drone manufacturer, Draganfly Inc, to develop technology that remotely detects the key symptoms of COVID-19 – breathing and heart rates, temperature, and blood oxygen levels.

Within months, the technology had moved from drones to security cameras and kiosks, scanning vital health signs in 15 seconds and adding social distancing software to the mix.

In September 2020, Alabama State University became the first higher education institution in the world to use the technology to spot COVID-19 symptoms in its staff and students and enforce social distancing, ensuring they had one of the lowest COVID infection rates on any US campus. ASU President, Quinton T. Ross, Jr., described the software as a “godsend”.

Wearable devices to diagnose medical conditions

UniSA biomedical engineer Professor Benjamin Thierry is developing a range of wearable technologies capable of diagnosing conditions including preeclampsia, epilepsy, fetal arrhythmias and heart attacks.

Through an NHMRC Investigator Grant, Prof Thierry hopes these technologies will help address the significant health outcome disparities across the country, which sees Australians living in rural and remote areas experience higher levels of disease and reduced access to health services, compared with their metropolitan counterparts.

“Wearable consumer products such as the Fitbit are already mainstream, yet the enormous transformative medical potential of wearable technologies is yet to be realised,” he says.

“There is a huge opportunity for us to create wearable devices capable of better diagnosing and monitoring medical conditions, particularly in rural and remote settings where patients often do not have access to the testing and specialist care that is available in cities.”

The wearables will use a cutting-edge solid-state sensing technology called Field Effect Transistors, which can measure bioelectric signals with extreme sensitivity when implemented at the nanoscale.

Supercharged bandages to revolutionise chronic wound treatment

World-first plasma-coated bandages with the power to attack infection and inflammation could revolutionise the treatment of chronic wounds such as pressure, diabetic or vascular ulcers that won't heal on their own.

Developed by UniSA, the novel coating comprises a special antioxidant which can be applied to any wound dressing to simultaneously reduce wound inflammation and break up infection to aid in wound repair.

With growing rates of global obesity, diabetes and an ageing population, chronic wounds are increasingly affecting large proportions of the general population.

Lead researcher, UniSA Adjunct research fellow Dr Thomas Michl, says that upgrading current dressings with this state-of-the-art coating will promote effective healing on chronic wounds and reduce patient suffering.

“Proper care for chronic wounds requires frequent changes of wound dressings but currently, these wound dressings are passive actors in wound management,” Dr Michl says.

“Our novel coatings change this, turning any wound dressing into an active participant in the healing process – not only covering and protecting the wound, but also knocking down excessive inflammation and infection.”

Augmented reality helps teens tackle anxiety

Augmented reality could help teens take control of their mental wellness, as UniSA researchers trial next generation technology in a push to curb increasing rates of poor mental health among Australian kids.

Funded by the Channel 7 Children’s Research Foundation, the world first research is testing the ability of augmented reality to improve the delivery of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) as a treatment for symptoms of childhood anxiety in kids with asthma.

Children with asthma are twice as likely to develop comorbid anxiety and/or depression, making them a high-risk group for poor mental health.

Lead researcher, UniSA’s Kelsey Sharrad, says the research hopes to show how augmented reality (interactive, computer-generated experiences overlaid across real-world environments) can enhance iHealth CBT resources to concurrently improve asthma and symptoms of anxiety among teenagers.

CBT is a first-line psychological therapy that uses practical, task-based processes to teach kids how to recognise and cope with feelings of anxiety but only 20 per cent of kids who could benefit from treatment are accessing it.

“Interactive technologies and personal devices such as iPhones, are a drawcard for most teenagers, so by developing novel iHealth solutions using augmented reality, we’re hoping to increase the appeal and engagement rates of CBT,” Sharrad says.

New app empowers mums to manage mental wellbeing

Recognising the symptoms of maternal anxiety and depression can be difficult, but with the help of a new app – developed with UniSA’s Match Studio – thousands of women will be empowered to monitor their mental health, both during pregnancy and after birth.

The YourTime app responds to priorities in perinatal mental health by providing a digitalised tool that enables women to self-monitor and track their mood during pregnancy and early mothering, helping them to recognise early signs of deteriorating mental wellbeing, or conversely acknowledge they’re doing well.

It is the first evidence-based app to help women track their own mental wellbeing throughout pregnancy and after birth.

Lead researcher and midwife, UniSA’s Associate Professor Lois McKellar, says the new app will provide immediate support for women who may be struggling with low mood, or beginning to experience anxiety and depression.

“The YourTime app will help a woman keep track of how she’s feeling during pregnancy and motherhood, enabling her to quickly recognise any changes in mood, behaviours or feelings,” Assoc Prof McKellar says.

“Guided by a midwife avatar, women will be able to monitor their wellbeing over time, access education and support materials, as well as connect to other women and mothers via a networking forum.”

You can republish this article for free, online or in print, under a Creative Commons licence, provided you follow our guidelines.