Article Lead In

22 November 2021

AUTHOR: WILL VENN

The impact of a pandemic and growing geopolitical tension in the Asia-Pacific is redefining how Australia relates to its neighbouring countries and long-term allies. How these partnerships evolve is crucial to both Australia’s prosperity as well as international security in the surrounding region.

For an island continent whose size, remoteness and mythology accentuate the value of ‘mateship’, making friends and building alliances is a key part of Australia’s identity and foreign policy.

Yet as the 2020s unfold, a decade so far characterised by the COVID-19 pandemic and rising geopolitical tensions in the Asia-Pacific region, for Australia to maintain – let alone advance – international economic and strategic relationships, is a balancing act requiring constant recalibration.

In September, the formation of a trilateral security pact between Australia, the UK and the US, known as AUKUS, strengthened a key strategic partnership for Australia but weakened a key economic one.

China, still Australia’s largest trading partner, despite worsening trade relations, described AUKUS as undermining regional peace and stability while intensifying an arms race.

Dr Daniel Biro, who lectures in global politics at UniSA, says AUKUS needs to be considered in the context of Australia’s successful reorientation of its foreign policy in “searching for security not from Asia, but within Asia” over the past few decades.

“The idea behind this line is often used in describing a fundamental shift in Australian foreign policy,” Dr Biro says.

“It is used to articulate the fact that since Federation and until quite late in the Cold War, from a security perspective, the Australian establishment had a tendency to perceive the threats to, and thus the vulnerabilities for Australia, as coming from Asia, as illustrated by the involvement in the wars against Japan’s regional ambitions in the Second World War, North Korean aggression in the 1950-1953 war, or communist Vietnam in the 1960s.

“However, particularly successful during the Hawke-Keating administration, Australia’s foreign policy efforts concentrated in working to expand relations with Asia in general, and with the ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) countries in particular.

“Between the 1980s and 2000s, there were significant successes in Australian diplomacy to do with a heightened presence of Australia in Asia – including the formation of APEC (Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation), ASEAN Regional Forum and East Asia Summit, not to mention the Cambodian peace settlement or the initiation of the Bali process.”

In this way, Australia switched from being the “odd man out in Asia” (as former Australian diplomat Richard Woolcott once described it) to being accepted and respected as an Asian country. Thus: “searching for security within Asia”.

“The sudden advent of AUKUS – regardless of what form these plans will take in the future, may once again raise some challenges to the way Australia is perceived in the region,” Dr Biro says.

“There is of course a risk that Australia is perceived as looking back in time, to its Anglo-American friends, rather than to the region.

“It is not a guarantee that this is how Australia is or will be perceived, but there is a risk given the manner in which the AUKUS initiative took place, and particularly the rather odd role of the UK in this initiative.

“Of course, these risks can and should be alleviated with an active and nuanced regional diplomacy in which Australia would be able to reassure (through words and deeds) our partners in the region, particularly countries like Indonesia and Malaysia, which have expressed reservations in relation to the effects that initiatives like AUKUS may have on regional stability.

“Worryingly though, despite recent initiatives like the Pacific Step-Up, there are various aspects that raise important questions about the willingness or the capacity of Australia to engage in that much needed type of regional diplomacy, under the current government.”

Australia’s diplomatic deficit

Dr Biro highlights the 2019 “negative globalism” speech of Prime Minister Scott Morrison at the Lowy Institute, the lack of consultation with regional partners before the launching of various recent diplomatic initiatives and the appearance of a neglect of ASEAN in favour of new initiatives such as the QUAD and AUKUS as examples of this.

“At the same time, for decades the Australian diplomatic service has been starved from appropriate funding, with one study last year pointing out to the fact that Australia has one of the smallest diplomatic networks among its developed peers,” Dr Biro says.

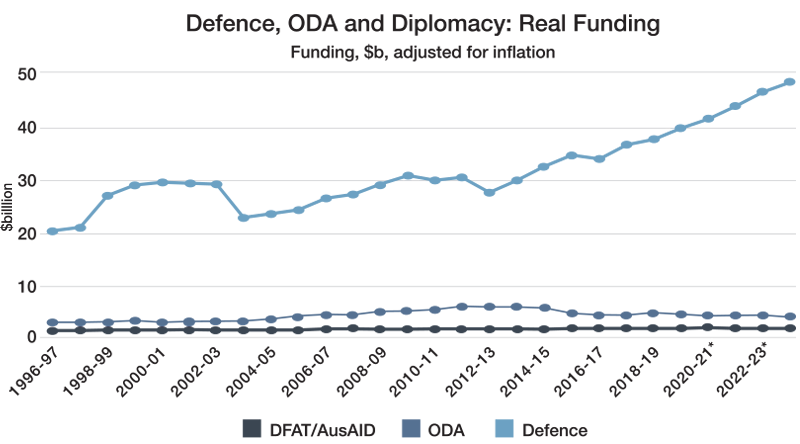

“A phenomenon portrayed for more than a decade now as an Australian diplomatic deficit, the severe decrease of the budget for diplomacy and foreign aid in the past decade offers a stark contrast with the increased spending on military and defence budget – which no doubt a commitment to the AUKUS nuclear submarine deal will only further significantly increase.”

The value of strengthening nuanced regional diplomacy extends beyond strategic considerations and takes in economic relationships as well, especially those which have been impacted because of COVID-19, due to border closures and flight bans.

UniSA Professor of International Business Susan Freeman says the pandemic has exposed the risks of Australia’s reliance on global supply chains. Prof Freeman was principal author of the 2021 Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (ACCI) National Trade Survey Report.

“There are some tremendous advantages to Australia being an island, as we’ve seen at the start of the pandemic, you can close off the country quickly,” Prof Freeman says.

“But there is also a downside to being an island of 25 million people – we enjoy a lot of the success we have economically because we are globalised and interconnected with so many economies around the world.

“The minute you close that down through the locking of borders – interstate as well as global borders – then our economy starts to shake.

“The pandemic has shown how reliant we are on interactions with our trading partners and the (ACCI) National Trade Survey Report indicates the huge impact this has had, for example, on our tourism sector and the international education sector.”

Australia’s dependence on regional trading partners

Education and tourism are Australia’s fourth and fifth largest exports, yet Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) data indicates the value of Australia’s onshore international education sector alone had dropped by $8.6 billion at the end of the first year of the pandemic.

“We are not a country in the middle of Europe with neighbouring economies where we can trade and we are not sitting in the middle of Asia,” Prof Freeman says.

“We are very dependent, more so than other economies, on having our borders open, to keep the flow of goods coming in for our manufacturing and production, service processes, education, tourism and hospitality, and skilled workers.

“The minute you close down a border, you say to a company, you can’t trade. You can’t do it all on the internet, there are some fundamental things about building relationships and trust that need to be done face to face.”

More than 200 Australian businesses were surveyed and 30 plus business founders/CEOs were interviewed for the 2021 national trade report, which found that structural reform is necessary for Australian businesses to grow and establish links with new trading partners, including those in Europe, Africa and Latin America, to help offset a strong reliance on China.

“As we're thinking about our place within this region, Australia doesn't understand at the political and at the ambassadorial level, just how skilfully this needs to be achieved,” Prof Freeman says.

“Many companies I'm speaking with say it's difficult to find people in the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) to assist and help them with the introductions that can help build new customer and new supplier relationships.”

DFAT reports that China is Australia's largest two-way trading partner in goods and services, accounting for nearly one third (31 per cent) of Australia’s trade with the world, yet that trade declined by 3 per cent in 2020. Australian goods and services exports to China totalled $159 billion in 2020, down 6 per cent compared to 2019.

Economically the benefits of diversification and extension of trade to other regional neighbours could help offset this decline, despite differences in political ideologies across the region.

UniSA Senior Lecturer in International Studies Dr Adam Simpson says such relationships need to be handled sensitively.

“Being a country with strong liberal democratic values can potentially put Australia at odds with some of the more authoritarian and semi-authoritarian governments in Asia,” he says.

*Projections based on forward estimates

Source: Defence and DFAT annual reports, portfolio budget statements and appropriations, Devpolicy Aid Tracker. ABS GDP and CPI data.

The balancing act that is non-interference

“Vietnam, Laos and China are governed by communist parties, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand and Cambodia are illiberal or semi-authoritarian,” Dr Simpson says. “Indonesia, the Philippines and the Northeast Asian countries of Japan, South Korea and Taiwan are considered democracies, so there is a real mix across the region.

“But there just isn’t the deep history of liberal democracy embedded in the region. Consider ASEAN and its 10 member states. Unlike in Europe, for instance, where the European Union (EU) penalises member countries that seek to undermine democratic practice, what underpins ASEAN is the principle of non-interference in other states’ internal affairs.

“Australia has a strong history of liberal democracy, of media that is free to criticise the government, yet that does not exist in many other countries.

“So Australia has managed its relationships with countries in the region by, in effect, adopting the ASEAN dictum of non-interference and not being too critical of their actions.”

Dr Simpson points to the recent military coup in Myanmar and the differing responses from other democratic countries to that event as providing an example of the way Australia adopts a more pragmatic approach to diplomacy in the region.

“The US and the UK are very critical of the military regime and putting sanctions on military personnel, but Australia is treading very softly here by comparison, using back channels with Singapore, Indonesia and other countries to try and influence outcomes.

“The shared values between the US, UK and Australia are evident by the recent AUKUS agreement, which may complicate regional diplomacy and increase the regional arms race, so Australia needs to reassure the countries in its own backyard of its peaceful intentions.”

But treading softly does not mean Australia should compromise on principles. Dr Simpson says that different values in China and Australia mean good diplomatic relations should not always be maintained at any cost.

“China is a single party authoritarian state that makes no real pretence of democracy and we have historically made an accommodation with it to pursue our economic interests,” he says. “This has been mutually beneficial in the past and can continue to be so.

“However, we also need to emphasise the liberal democratic values which Australia is founded on, including free speech and free media, and this might mean enhancing the diversification of our economic interests across other countries in Southeast Asia.

“Indonesia, for example, is our nearest large neighbour, comprises a population of 270 million and has made great strides in democratic values over the past two decades – although these are under pressure.

“We should be endeavouring to engage with the country much more strongly to further both our economic and strategic interests and help consolidate democratic values.

“We still need China but we shouldn’t rely on China. It’s easy to make friends internationally by never criticising anyone but we shouldn’t abandon our values for the sake of an economic relationship with another country.”

True partnerships are generally founded on an alignment of values and ideals, but if there is risk of those being significantly compromised, whatever the nature of the strategic or economic arrangement, breaking up isn’t necessarily a bad option.

Or, as Dr Simpson says: “It’s a delicate balance but sometimes diplomatic relationships need to deteriorate to make that point.”

Further reading:

- ‘Two governments claim to run Myanmar. So, who gets the country’s seat at the UN?', The Conversation

- ‘ASEAN finds its voice as a military offensive looms in Myanmar’, The Strategist, Australian Strategic Policy Institute

- ‘Myanmar’s exile government signs up to ICC prosecutions’, East Asia Forum

- ‘How a perfect storm of events is turning Myanmar into a ‘super-spreader’ COVID state’, The Conversation.

- ‘With Aung San Suu Kyi facing prison, Myanmar’s opposition is leaderless, desperate and ready to fight’. The Conversation.

- ‘Treating the Rohingya like they belong in Myanmar’, The Strategist, Australian Strategic Policy Institute

You can republish this article for free, online or in print, under a Creative Commons licence, provided you follow our guidelines.