Article Lead In

22 November 2021

AUTHOR: CANDY GIBSON

Government and business are being targeted by ever more sophisticated cyberattacks. Working in partnership with others could be the solution.

The word hacker conjures up images of nerdy computer geeks in hoodies, hunched over their PCs in a back room in Russia, quietly and devastatingly bringing a company to its knees in a matter of minutes.

Half of that sentence is probably true, but the reality is more frightening.

A global army of skilled, sophisticated IT wizards from all walks of life and nationalities is now holding the world to ransom – literally – by engaging in the fastest growing form of modern warfare.

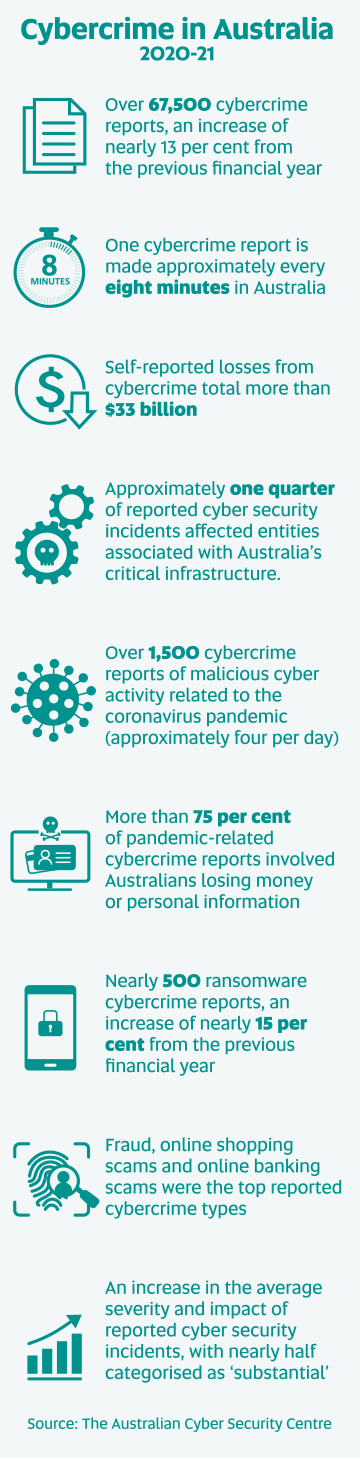

In 2020, cybercrime cost the Australian economy an estimated $29 billion, or almost two per cent of the country’s GDP. Globally, that figure blows out to $1 trillion.

The eye-watering stats are hard to comprehend for people who have never fallen victim to a hacker, although 6.7 million Australians won’t be surprised by the revelation.

UniSA became one of those statistics in May 2021, when a Russian ransomware attack disrupted parts of the network for several weeks.

UniSA Chief Information Officer Paul Sherlock says the initial external reaction to a cyberattack, like the one UniSA experienced, is often misplaced. Fortunately, the damage was limited because of the University’s quick actions and IT expertise, but the incident exposed the risks that all organisations face, particularly those with valuable information.

“People assume that your systems are not secure and the fault lies from within, but the fact is that thousands of highly successful businesses – and governments – are being hacked every day, despite considerable resources and money allocated to IT security,” Sherlock says.

On average, companies ring-fence between six and 10 per cent of their IT budgets for cybersecurity, depending on the risk. In the software publishing, banking, and financial sectors, this can amount to millions of dollars.

And, still, it feels like the world is playing a game of whack-a-mole; disrupting major hacks to governments and corporations, only to uncover another one lighting up the map elsewhere.

In the past year alone, Australia has seen a major television network targeted (Nine Entertainment), JBS Foods (the world’s largest meat supplier), and two attacks against logistics company Toll Holdings.

The damage has been ‘catastrophic’, the head of the Australian Signals Directorate (ASD), Rachel Noble, told a Senate committee in June, and there’s no sign of the threat diminishing. Quite the opposite.

Noble cited a 60 per cent increase in ransomware attacks against Australian entities between 2020 and 2021, by state-based actors as well as criminals.

The motivations are not just money, either.

Source: The Australian Cyber Security Centre

Cyber criminals aren’t always after money

“The bad guys come in different varieties,” Sherlock says. “Some are just seeking to embarrass you (hacktivists); some want to take down your website for revenge or pure thrill seeking; some are looking for sensitive information; and then there are the organised crime gangs who are simply looking to make money.”

A 2020 survey by cybersecurity company Crowdstrike found that more than two-thirds of Australian organisations had suffered a ransomware attack in the previous 12 months – higher than the rest of the world. Yet only a third of them went public with it.

“The lack of transparency is part of the problem,” Sherlock says.

“Organisations that experience cybersecurity attacks need to stop thinking like victims. We can no longer deal with these attacks in secret. We need to share information and work with multiple partners if we are to get on top of cybercrime.”

When UniSA systems were attacked in mid-May, the University immediately notified all Australian universities, as well as police, government, and relevant intelligence agencies.

Sherlock says by alerting all parties and sharing information, everyone in the sector was put on notice, reducing the chances of a successful attack elsewhere.

“You don’t even have to release every single detail of the attack. With a few breadcrumbs, cybersecurity people are clever enough to work out what has happened and then use that information to assess their own defence. So, sharing information is absolutely critical.”

UniSA is also connected with key industry bodies tasked with remediating attacks and identifying threats. It is this community mentality which will – if not win the war, at least hold the attackers at bay.

At the heart of the cyber crisis is the world’s increasing reliance on the internet. Almost everything is underpinned by digital delivery, whether it’s banking, entertainment, shopping, social media, emails, studying, or accessing medical records.

Bec Medhurst, a former police officer, intelligence analyst and prosecutor, who now teaches cybercrime and digital evidence as part of UniSA’s Bachelor of Criminal Justice, has an example. In fact, it’s virtually impossible to get through a single day without using a digital service.

“We wake up, check our emails and news feed, drive to the shop, where we use our phone to QR code in and use payWave to buy a coffee. Just doing all that pings our location, how we got there and what we did,” Medhurst says.

“If we then send a text or upload something to social media, that is showing a pattern of life. By infiltrating our phone, a cyber actor will know what we’re doing, where we’re going, even how we’re feeling. The artificial intelligence algorithms are now so sophisticated that they can probably predict our next steps.”

So, going off grid really isn’t an option. The world is hooked into cyberspace and there’s no turning back.

However, there are steps that individuals and companies can take to limit the risks of digital breaches, Medhurst says, and it requires cooperation between multiple parties.

“Frequent and robust password changes and antivirus software are the PPE and vaccine equivalents to protect us from a cyberattack.

“Being aware of scams and teaching vulnerable groups about internet security is everybody’s business. Companies also need to ensure they do a regular IT health check.”

The Australian Internet Security Initiative (AISI) acts as a kind of internet service provider neighbourhood watch, helping to raise security levels on national IP addresses. Internet service providers submit metadata to the site when they’ve noticed specific vulnerabilities.

The service has highlighted some major threats in recent years, Medhurst says, but like all initiatives, its success relies on cooperation.

While business, industry and police are upping their game in the cybersecurity stakes, governments are letting the side down, mainly due to geopolitical differences with other nations.

The crossover of jurisdictions in investigating, charging and prosecuting cybercrimes is a quagmire, Medhurst says. Victims and offenders are often in different countries, complicating the process.

The Budapest Convention, drafted 17 years ago when the world was less connected, is the closest framework for a united global front to fight cybercrime, but not every nation is a signatory.

The exponential growth of digital connectivity since 2004, including the billions of physical devices now connected to the internet, along with the development of cloud computing, has created some major headaches for global law enforcement.

In response, the treaty is being updated, requiring participating countries to adopt certain evidence-gathering rules, but there are still some gaping disconnects in accessing data.

Medhurst says the potential for a global disruption of infrastructure is frightening and all too real.

“What we are wrestling with is a major shift in crime and motivations,” she says. “The reasons someone commits a cybercrime may be very different from a traditional crime, and from a law enforcement perspective, have made it far more difficult to tackle.

“The consequences of some of the cybercrimes being committed now, including theft of data, may not be realised until years down the track. Once someone’s got data, it can be sold to a third party. Depending on where it ends up, the result can be catastrophic.

“The targets are exponential. One criminal event from a hacker can affect millions of victims in one fell swoop. And every technological innovation we take to address the problem can potentially be exploited. We have to come to terms with that.”

Satellites could be the next target

There are more than 7000 of them orbiting the earth and a scary percentage of them are unsecured. UniSA SmartSat Chair in Cybersecurity Professor Jill Slay is at the forefront of the next domain for cybercrime – satellites.

When you think of their multiple uses – sending television signals directly to homes; enabling pagers and mobile phones in remote areas; steering people to the right location; providing instant credit card authorisation; forecasting the weather; predicting climate change; and basically, helping people communicate with the world – society’s dependence on them is increasing by the day. And so is its vulnerability.

The proliferation of satellites and the lack of stringent security attached to them is an open invitation to hackers, Prof Slay says, and a risk that governments are still grappling with.

“Many of the devices attached to the Internet of Things (IoT) via satellites are made cheaply in Asia, connected to trillions of sensors, yet without any anti-virus, firewalls or other security applications that could protect them,” Prof Slay says.

Some of the big hacks have been through cameras on laptops, where millions of machines have been hijacked for their computing power to make cryptocurrency, which requires massive amounts of processing capacity.

Even dairy cows pose a risk, with hackers successfully harnessing the power of thousands of tiny chips embedded in health tracking devices attached to their ears.

“It sounds ridiculous but it shows that embedding ransomware or other malware on a network is not the only form of cybercrime. Hackers are just as likely to want to steal your processing power.”

Prof Slay says the only way to protect systems from being hacked is to adhere to a strict code of training standards, and for governments, industry, and business to play their part.

“Individuals and corporations can be attacked in so many ways – through their hardware, software, telecoms and networks. To make it harder for cybercriminals we need far tougher security regulations, including background checks on all employees.”

Governments also need to press pause on the burgeoning satellite industry and address the security gaps before launching more satellites into space, Prof Slay says. The alternative is to keep allowing nation states such as China and Russia to park their satellites in orbits next to ours and suck out the data.

Given society’s complete reliance on a digital world, is there room for optimism in this modern-day war?

Yes, there is, says Sherlock.

“There are many things that we can do that will make it harder for cybercriminals. Like all wars, it depends on who has the most up-to-date information, the best weapons, and the strongest allies. But will we win the war? That’s up to all of us – cybersecurity is everyone’s business.”

You can republish this article for free, online or in print, under a Creative Commons licence, provided you follow our guidelines.