Few could forget the haunting images to come out of Australia’s catastrophic bushfire season of 2019/2020. The entire populations of some towns huddled on beaches, seeking shelter from the fire front, while small children wore facemasks, backlit by a reddened sky. The images put faces on a disaster of such scale that it seemed impossible to comprehend.

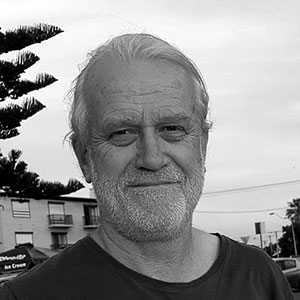

For University of South Australia researcher Dr Johannes Pieters, the scenes from last summer take him back to his own experience as a young boy growing up in rural Victoria. He vividly remembers kneeling next to his parents and sister on the front lawn of their home and being told to pray as a bushfire raged nearby. Thankfully, it rained, and the fire was controlled – but 33 people died and 450 houses were lost. His childhood summers were always accompanied by a latent fear of the ever-present danger of bushfires. A whiff of smoke on the air raised questions and anxiety levels – where was it coming from, how far away was it, do we need to leave?

It’s an experience Dr Pieters shares with the hundreds of thousands of Australians who took shelter last summer as fires threatened the communities they call home. Some, like Dr Pieters, were lucky – escaping with their lives and homes intact. Others were not.

By the end of the 2019/2020 bushfire season, 33 people had lost their lives and more than 3000 homes were destroyed. The widespread devastation united the country as Australians everywhere banded together to do what they could for those affected.

But as embers cool and the media circus moves on, what happens next for the hundreds of regional communities where lives, homes and businesses have been destroyed? What are the short- and long-term impacts and what can be done to help communities recover? Is it even possible to recover or rebuild after such destruction?

This time, Dr Pieters turns to his professional experience. The urban, regional and social planning expert conducted research on the ground in Marysville one year after devastating bushfires virtually wiped the town off the map and killed 45 people in 2009. Dr Pieters was there to explore how meanings of home can influence people’s recovery from bushfire-related housing loss which he suggests involves three processes that address the material and psychological aspects of displacement: re-establishing a sense of belonging, a sense of spatial identity and a return to routine.

“I argue that regaining a sense of home is central to these processes of recovery, and research suggests that home can mean many things – where you find security or comfort, a base, a safe haven, or a place tied to your identity,” Dr Pieters says.

“That sense of home isn’t necessarily linked to the bricks and mortar of a building and that’s why we found some people were able to regain that sense of home, despite losing everything in the bushfire."

Through in-depth conversations with the survivors, he uncovered that being able to find meaning or significance in the wider area or community was what helped some feel settled again.

“The environment – and Marysville is naturally beautiful environment – contributed to that sense of home,” he says.

“For many, it was also an area that held significance in their life – it could have been the place where you grew up, where you got married, or where other major life events took place – that personal history in the region offered a sense of home through that feeling of continuity.

“What became clear was that for many, home wasn’t just about a house, it was also about the environment around you, the community you are a part of, and the services – schools, hairdressers, mechanics – you have access to. That’s how some of people I interviewed were able to regain a sense of home despite the loss of their house – by finding that the area in general still held some sort of important meaning and gave them a sense of community.”

A growing sense of community – and more awareness of communities beyond our own doorstep – is what Executive Dean of UniSA Business, Professor Andrew Beer, hopes will play an important role in ensuring regional communities not only recover but prosper following the bushfires. An expert in the drivers of regional growth, Prof Beer says an increased connection between metropolitan and regional communities is one of the few silver linings of the most recent bushfire season.

“I hope this is the lightning rod for change in regional communities around Australia, who have for years faced a number of challenges, from drought and floods, to ageing populations and higher unemployment,” he says.

“One of the few bright spots to emerge from that summer of devastation is the fact that the broader Australian community has forgotten the long-held divisions between Sydney and the bush, or between metropolitan Australians and those in the regions.

“Now more than ever before, Australians have to reconsider themselves beyond the very narrow place of residence and place of employment to reach an acknowledgement that we all have a shared future.”

Much of Prof Beer’s research has been dedicated to understanding the importance of regional Australia for the country’s overall economic success and factors that influence regional growth. He wants the attention regional Australia has received because of the bushfires to bring about real change in the way governments approach regional areas, better reflecting the critical role they play in the nation’s continued prosperity.

“The real issue is not about just rebuilding, it's about rebuilding better,” Prof Beer says.

“What that looks like is being smarter in terms of the structures we build, how we support the affected communities, and of course, where we rebuild. This summer has clearly illustrated we have to be far more intelligent about where we plan for development to take place and how it takes place.

“If we can find solutions for regional Australia, we find solutions for Australia.”

Prof Beer is calling for a federal government-led initiative that addresses the challenges facing regional Australia with key focus areas such as infrastructure investment, workforce development, and the creation of new industries. But he is quick to point out that for such an initiative to work, there needs to be constant engagement with, and support for, regional communities.

“We're never going to get an effective response unless we have people on the ground, taking ownership and responsibility, and addressing the challenges and finding their own solutions,” he says.

“The central governments then need to come in behind them and support them with financial resources. Local leaders – and it’s not necessarily the local government leader, it could be a prominent business owner or community volunteer – bring other resources to the table. They bring their local knowledge, connections with other parts of the community that they live in, and external links to the city.

“A vibrant community is one that either has growth or has the potential for growth but perhaps the most essential ingredient for a successful community is a shared sense of what it is and where it's going. Often that sense of community can only come from within. We need to keep that front of mind as we consider how we rebuild the communities that have been devastated by bushfires.”

With this year’s bushfire season fast approaching and a global pandemic still raging, it is more important than ever to consider the communities around us and how we can work together to face the challenges of our time – from climate change and bushfire prevention to regional, national and global economic decline – that affect us all.

As the National Bushfire Recovery Coordinator Andrew Colvin said: a national disaster needs a national response, but to be successful it needs to involve people and experts at every level – particularly those communities which were directly affected.

“Like every Australian experiencing our nation’s bushfire disaster, I am broken-hearted by the loss of life, the devastation to local communities, the casualties of livestock and wildlife and the immense pain and suffering of so many of our fellow Australians,” Colvin said.

“The impacts are so widespread that most of us will either have been affected in some way, or at least know someone who has been affected.

“The scale of this event means that this is a national disaster. And the response therefore must be coordinated at a national level.

“The bushfires have ripped at the very fabric of our regional and rural communities. Solutions to rebuild, repair and re-establish must be designed and delivered with community at their heart.”

THE LAWS OF DISASTER

“How do we live sustainably with bushfires and other natural disasters as they become more severe and increasingly frequent due to climate change? Now is the time for long-term thinking – shifting our focus to preparedness by not putting people in the face of danger in the first place.”

These are the words of Professor of Business Law Jennifer McKay, whose research looks at ways the law can be used to promote ecologically sustainable development. For Prof McKay, the catastrophic 2019/2020 bushfire season wasn’t a surprise; it was almost inevitable in an environment where communities, governments and other stakeholders – with varying priorities and resources – are not united in addressing the challenges of climate change.

The tangled web of players involved in keeping the country safe from natural disasters is highlighted in a background paper released by the Royal Commission into National Natural Disaster Arrangements in May:

Australia’s natural disaster arrangements are characterised by a layered and matrixed system of governments, organisations and communities, where roles and responsibilities are shared between public and private entities. While states and territories have primary responsibility for emergency management in their jurisdiction, every level of government has some role in preparing for, responding to, and recovering from natural disasters. Individuals, non-government organisations and private industry also play an important role.

Prof McKay sees law reform as an important way to help diverse stakeholders from across the country work together to improve Australia’s preparedness for bushfires – and she says the key lies in a mandate called the precautionary principle.

UNESCO's World Commission on the Ethics of Scientific Knowledge and Technology defines the precautionary principle as: When human activities may lead to morally unacceptable harm that is scientifically plausible but uncertain, actions shall be taken to avoid or diminish that harm.

“Essentially the principle says that if there’s scientific uncertainty about whether something is safe – in locating a new development in a hard-to-reach valley, for example – you should not do it,” Prof McKay says.

“There's a general understanding that Australia’s processes in land use planning so far have not been good for disaster prevention.

“Going forward, we need a precautionary approach to land use development by using the precautionary principle, which can already be applied in all states and territories but is rarely used.

“The federal government needs to step in to dictate how states and territories apply the precautionary principle so that we’re all on the same page when it comes to keeping people safe from the very real threat of bushfires.

“Every time there is a bushfire, there’s footage on TV of people planning to rebuild in the same place their house has just burned down. While this might be a feelgood story, it’s not always the best decision. Individuals, developers and governments need to be far more cautious about where we build in the future.”