20 June 2025

AUTHOR: Will Venn

> BREAKOUT STORY: Making scents of our memory

When the radio plays hits from your teenage years, it’s easy for your mind to wander back to that period of your lives with vivid recall.

Music is a powerful trigger for memories, but in particular, the age of 17 has been pinpointed as the peak era for listening to new songs that, in later life, will reap the most nostalgic rewards.

This is the outcome of research from the University of South Australia’s Ehrenberg-Bass Institute for Marketing Science, whose experts in evidence-based marketing understand the high value role that nostalgia-triggering tunes play in advertising and brand awareness.

Researchers initially examined several studies, dating back decades, that showed how influential age can be as a key predictor of music preferences and what the critical period of time is when those preferences take hold.

They then undertook their own research (with added relevancy in the era of music streaming, where on-demand access to music has massively expanded the song choices available to listeners) and made some interesting discoveries.

Edge of seventeen

It was found that individuals prefer popular music from their mid-to-late teens most of all, with music released earlier or later in their lives commanding less love. Age 17 was determined to be the prime time for making musical memories, with the flip side being 35 – the age at which we start to tune out of listening to much new music.

Dr Bill Page, Senior Marketing Scientist at UniSA’s Ehrenberg-Bass Institute for Marketing Science, explains the research methods that he and co-authors Carl Driesener, Callum Davies, and Zac Anesbury undertook:

“We had 1000 people share their responses upon hearing snippets of 34 songs selected from the Billboard Top 10 charts from 1950 to 2016, with preferences assessed on a 10-point scale,” Dr Page says.

“The songs selected were intended to be representative of the year that they were hits, so within the top four to 10, but not the top three songs of the year. To avoid the influence of outliers, we excluded songs that were so popular that they 'transcended' their year of origin – think Queen’s Bohemian Rhapsody.

“Then, after taking into account the song-specific-age (a measure of the respondent’s age when each of the 34 songs featured in the top 100) calculations were made, which indicated preferences for popular music peak at around a period of mid to late adolescence, specifically 16.7-16.8 years of age.”

Associate Professor Carl Driesener, also of the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute, says the findings are consistent with previous research.

“The kind of research that we do at the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute is really about that sort of replication and extension. So what has previously been done before? And if we tinker around the edges to try different circumstances and contexts, do we find the same thing?”

“If we look 20 or 40 years later from the time of audio cassette tapes to music streaming, are we still finding the same effect? When we do find the same thing over and over again, it's a generalisable pattern and therefore we can have a lot more faith in these results."

Twenty-four had the floor

However, it appears nostalgia isn’t quite what it used to be. The findings do contrast slightly with earlier research from the 1980s, which showed a preference peak of 24 years. That was the decade in which compact discs started to gain ubiquity, but their initial cost made them more a source of entertainment for cashed-up yuppies rather than cash-strapped teenagers, with the advent of music streaming still more than a couple of decades away.

“Given the quantum shifts in music consumption and the increased accessibility of music offered by digitalisation and streaming, a lowering of the peak age is conceivable,” Dr Page says.

“An increased exposure to music at a younger age and greater availability to music of all ages could be contributing factors to this shift of preference, but additional research would be required to determine this.

“Anecdotally, I think most people would say their favourite music is from their late teens or early 20s, and then later in life people will often say, this new music that’s coming out now is just awful. But is it really? Or are you predisposed to thinking that from a certain age?”

Whose good old days?

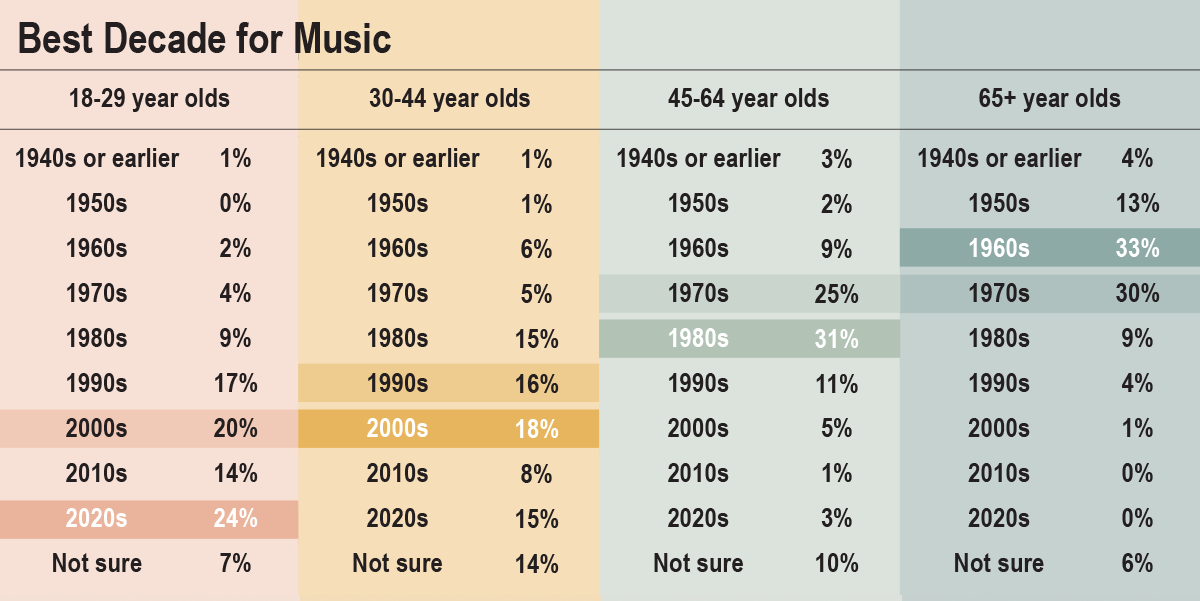

The research was highlighted in a Washington Post article, which defined “the good old days”, or nostalgia for a particular period of time, as being related less to that specific era itself and more to the age a person was at that point in time. So, for those born in the 1980s, the best time for music was in the late 1990s. For those born in 2007, Charli XCX’s Brat album may one day be a source for misty-eyed nostalgia.

“We do know that memories are formed more easily when there are more emotions going on, or when there are new experiences to be had. In young adulthood, that's when there are many of these new experiences, of getting to go out into the world and doing things for the first time,” Dr Page says.

“It may not be the first time someone listens to music, but it could be the first time they choose to listen to music as opposed to hearing it in the car with mum or dad and the radio on,” he says.

Assoc Prof Driesener points out that while 17 may be the golden age for forming music memories, that doesn’t necessarily extend to other areas; one example being a recent article in New Scientist stating that the best retro games console is the one you played at the age of 10.

“Some of the research done by others in different categories indicate an earlier age, like political preferences get set earlier, and with other categories it’s a bit later, so it’s not like everything happens at 17, it's just that music happens to be around 17,” Assoc Prof Driesener says.

From radio stations dedicated to playing the hits of specific decades, to almost any form of advertising, the deep connections and associations music creates, serves as an emotional prompt linking long-held memories to places and products.

To maximise audience potential through music, Assoc Prof Driesener says that it is generally the hits from the past, rather than those from the present, that can increase engagement in adults.

“For example, if you were targeting 35-year-olds, you want to be playing something from when they were 17 rather than the present day.

“More generally, though, you want to be playing older music that spans several years rather than from one particular year because, if you're only targeting 35-year-olds, you're missing a larger audience either side of that age bracket."

Where once muzak sounded out in public spaces, elevators and shops across the world, today supermarket-branded radio stations tapping into the hits of yesteryear are triggering nostalgia in the shopping aisles, digging new grooves to purchasing power.

Clearly the music you heard at the age of 17 isn’t just shaping those personal playlists of today, but will also shape consumer behaviour for years to come.

Making scents of our memory

MOD.’s current exhibition: Forever, is about experiencing time in new ways and its street gallery prompts visitors to retrieve memories not through music, but through the power of scent.

Artists Elizabeth Willing and Dirk Yates explored the idea of scent memory, creating a “Scent Memory Database” inviting visitors to the gallery to smell labelled scents stored on shelves, each layer holding different aromas that also mix to create new combinations.

The labels are intriguingly named and serve as scent prompts, examples including; hot cross buns, equinox moon, deck resealing, footy changerooms, and bonfire barbecue.

UniSA PhD candidate Hayley Caldwell, who is based at the Cognitive Neuroscience Laboratory at UniSA, works with 'retrieval cues' to investigate how we stabilise and enhance memory during sleep and they explain the science behind scent and memory.

“Smells are the most effective retrieval cues as they are the only sense to completely bypass the brain’s sensory gating mechanism – the thalamus – to then be processed more closely than any other sense to the hippocampus, our brain’s memory hub,” Caldwell says.

“Above the nasal cavity at the base of the brain sits the olfactory bulb. This bulb is a group of cells which help us interpret smells. It has a direct connection to the hippocampus and amygdala, key regions of the brain involved in memory and emotion. This makes smell a strong sense for memory recall.

“So, if these smells made you think of a specific time in your life that means they acted as retrieval cue, which help us to access our memories in a process called memory reactivation.”

In this way, although curated by artists, the scents prompt visitors to recall their own scent memories, creating a personal journey through time, says Exhibitions Lead, Claudia von der Borch.

“We know that music is a great retrieval cue for memories, but at MOD. for this exhibition we chose to focus on scent, trying to capture something that is almost transient,” von der Borch says.

“Memory and nostalgia are important for our sense of time and our perception of ourselves and our identity. The playfulness of nostalgia in the street gallery section has been evident in the reactions of people who have visited, and the stories that they tell each other of what these different scents remind them of.

“It’s a popular part of the exhibition and a lot of young people have come in and connected with friends and family over the memories it evokes”.

You can republish this article for free, online or in print, under a Creative Commons licence, provided you follow our guidelines.