13 July 2023

AUTHOR: Will Venn

The aspirational “Australian Dream” of home ownership, propagated in TV clips since the 1950s, has been displaced this decade by TikTok reels detailing the blunt reality of families forced to inhabit tents in caravan parks.

Australia’s housing crisis is a multi-faceted issue that appears intractable, but research is finding the historic fault lines that have led to the current situation, building the knowledge, if not the bricks, that will be essential to solving it.

In late 2022 Patricia Thompson posted a series of videos on TikTok which generated millions of views depicting how her partner, their five children and herself had adapted to living in a tent in a caravan park in New South Wales.

But this wasn’t a holiday. The family was forced to secure alternative accommodation after their rental home required urgent repairs.

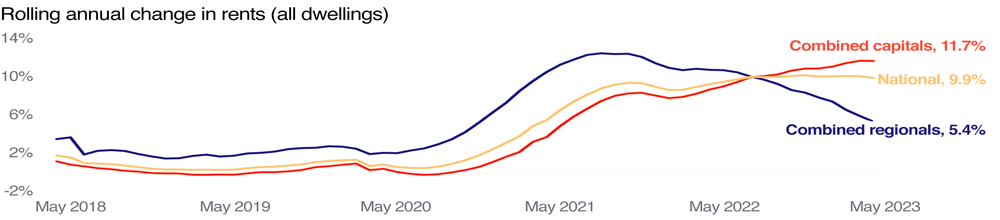

Thompson’s story, far from unique, was reported by media outlets across the world as being emblematic of Australia’s housing crisis, a crisis defined by spiralling house prices and rental costs, a chronic shortfall in new housing (exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic), a rapidly diminishing supply of vacant rental properties and a leap in mortgage rates between 2022 and 2023.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics reported in March this year that the number of Australians experiencing homelessness has grown by 5.2% in the five years to 2021.

Identifying the causes of the crisis and finding solutions to them are significant challenges, but ones that the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI) Research Centre at UniSA has in check.

The Centre, which forms part of a wider network of nine university partners, provides research that supports policy development on issues including homelessness, economic productivity, urban planning and infrastructure development, housing supply and affordability.

Origins of today’s housing issues four decades in the making

UniSA senior lecturer in property Dr Braam Lowies, a former director of AHURI at UniSA, traces the background of the current crisis to the house price boom of the 1980s.

“Housing affordability shows the relationship between housing expenditure, such as mortgage payments, house prices and rents, and household incomes,” Dr Lowies says.

“Since the early 1980s, house prices have increased exponentially more than household income, leading to the decline in housing affordability that we see today.

“Added to this are rising rents, which lead to low rent affordability and availability, aggressive increases in property prices and increasing interest rates ... creating an untenable situation with high demand and low supply.

“This also flows through to the social housing sector with a low supply of social housing leading to a rapid increase in homelessness.”

(Social housing is affordable rental housing provided by the government and community sectors to assist people who are unable to afford or access suitable accommodation in the private rental market.)

In December 2022, the Australian Homelessness Monitor reported that housing affordability had been one of the fastest growing causes of homelessness, with a 27% rise over a four-year period (up to 2021-2022) in the average monthly number of people who access homelessness services due to their inability to pay rent.

First Nations Australians and those with mental illness are the two fastest growing groups of people using these services, increasing by 23% and 20% respectively over the same period.

Even for those able to secure accommodation, one in five low-income households are left with less than $250 to live on each week after paying the rent, according to the Australian Government Productivity Commission.

The dream of home ownership that flourished in the post-war boom era of assisted migration, when the house price to income gap was significantly narrower than it is now, seems an increasingly remote fantasy.

While property values in Melbourne, Sydney and Hobart have increased by 400% or more over the past three decades, the share of younger households owning their home has decreased significantly.

Dr Lowies says Australia has an entrenched ideology that places high value on home ownership.

Haves and have nots highlighted by generational differences

In Australian cities, where the majority of people live, there’s “a stark contrast between younger generations who are not homeowners and an ageing population holding most of the housing wealth”.

Dr Lowies says that the question of tenure and generational change is growing in importance, with inequalities in housing ownership experienced differently over generations.

“Younger generations in established economies, such as in Australia, are increasingly becoming renters.”

Renting is becoming the primary tenure for millennials, he says, with a significant portion of housing “locked-out of the market as households in the silent generation and baby boomers (and subsequently Generation X) age in place”.

“This locked-out stock and value of the housing asset (and wealth) imposes major constraints in particular on millennials, in their locational housing choice.”

What Dr Lowies refers to has been described as “intergenerational theft” by the Australian Greens. It’s an issue in need of rapid remedy, but what is the solution?

“In short, the answer lies within housing policy and how it is applied in Australia,” Dr Lowies says. “Policy is often misguided, favouring only certain age cohorts of the Australian population. An enhanced understanding of this and the specific impact it has on millennials, is needed, as different generations are respectively, unequally locked-out and locked-in to housing wealth.

“Focus is needed on developing a more nuanced housing policy to address these intergenerational differences. This may include revisiting wider policy issues concerning taxation and inherited wealth – an uncomfortable, but much needed conversation.”

AHURI was formed by the Commonwealth and state and territory governments in the 1990s to draw out these and other nuances, by providing evidence-based research for policy development on housing supply and affordability, urban planning, infrastructure development and homelessness.

AHURI’s national managing director, Dr Michael Fotheringham, says evidence-based policy solutions that state and federal government can apply, are being developed.

“We do this through a nationally competitive grant round to our nine member universities, which have leading housing and urban researchers, and through that we fund multiple projects each year for research and capacity building,” Dr Fotheringham says.

“We are the first point of publication for that research, and we then work directly with governments on how this evidence can inform their policy thinking and improve their programs. It’s a continuing cycle of knowledge generation and translation.

“There’s also a growing recognition that some of the policy settings that have been popular have not actually been helpful, like first time [home] buyer grants, that have inflationary effects on prices; so we’ve started to move beyond those knee-jerk reactions to more evidence-based approaches.”

Could a tree change or sea change be the solution?

Dr Fotheringham says low vacancy rates in the rental and property sales market are a challenge. This was exacerbated by the impact of COVID-19, which disrupted supply chains and slowed residential construction. However, the pandemic has also seen regional centres flourish.

“As the idea of working remotely has become a mainstream, accepted idea for many workers, the idea of living not in the city, but in a regional centre, becomes more appealing. What has been relatively cheaper housing and land in regional locations has become a bit of a magnet,” Dr Fotheringham says.

“There is a huge pull for people to leave big cities and move to regional centres.”

At its national summit in 2022, the Regional Australia Institute advocated for an extra 500,000 people to be living in the regions by 2032, to reach a regional target of 11 million.

“UniSA has been a leading contributor of evidence in what the drivers are for people to move to mid-sized cities,” Dr Fotheringham says.

“What is the decisional matrix that people use to make those moves and what are the implications on regional centres in terms of their urban planning, their population planning, and their infrastructure? These are important questions to consider if we are going to meet the needs of Australian households in the years ahead.

“The regional connectivity piece is a complex one that involves multiple layers of government and includes telecommunications connectivity, road and rail transport connection, and energy supply; these are important considerations for us to understand to provide for the choices people need to make.”

The AHURI report Growing Australia’s smaller cities to better manage population growth examines the capacity of Australia’s smaller cities to assist in managing population growth, including national and international migration.

The UniSA-led report, co-authored by UniSA Executive Dean of Business Professor Andrew Beer, highlights policy options including activating land use planning to support the development of smaller cities, concentrating investment in a limited number of smaller cities, and expediting the growth of smaller cities as preferred places of residence for older Australians, including retirees.

It reveals the disparity between Australia’s population growth in capital cities (which rose by 10.5% between 2011 and 2016) with that in the regions (which grew 5.7% in the same period), noting that this growth is contributing to the $19 billion in congestion costs affecting Australia’s eight capitals.

The report underlines that repopulating regional Australia is “not simply about increasing the number of people who settle in these areas” but requires that federal and state governments implement policies to develop local economies, and that such policies should acknowledge that each and every city, region and rural district offers distinct opportunities for advancing wellbeing and a development approach that is tailored to the needs of each place.

Importantly, place-based policy explicitly seeks the development of all parts of the landscape, with no settlement deemed too small or too remote to plan for progress.

Place-based policy is just one part of the solution, Dr Fotheringham says.

“There’s another way to look at housing, which is a cohort-based approach; different groups of people have different needs; youth homelessness is a quite different experience than the homelessness experienced by women and children who have escaped domestic violence. People with disabilities may require specialist disability housing.

“UniSA has done some great work particularly around the housing solutions for vulnerable older Australians, bringing understanding to what types of housing opportunities we could be creating for them.”

Aboriginal people worse off than other Australians with housing

There is also the substantial matter of homelessness in Aboriginal communities, with Aboriginal people 15 times more likely than other Australians to experience homelessness.

“It is an indictment on the country that First Nations housing outcomes are much poorer than newer Australians [recent migrants], so better long-term solutions for housing Indigenous Australians are a key area of focus, and UniSA has done some good work in this space,” Dr Fotheringham says.

That work includes the Urban Indigenous Homelessness: much more than housing report, which examines the causes, cultural contextual meanings and safe responses to homelessness for Indigenous Australians in urban settings. The report was co-authored by UniSA’s Professor Deirdre Tedmanson and identifies that the most important failure of service delivery to Indigenous populations is the lack of housing options.

“Although structural discrimination, mental illness and poverty can make it difficult for Aboriginal people to access and sustain housing, it is the lack of funding, affordable housing and limited crisis and transitional accommodation that are the real barriers,” Professor Tedmanson says.

“There is a lack of dedicated services for Indigenous Australians experiencing homelessness in urban areas, despite their acute over-representation. This combines with other systemic barriers to explain their overrepresentation among specialist homelessness services also.

“Western notions of ‘home’ and ‘homelessness’ don’t necessarily resonate the same way with Aboriginal Australians in regional and remote areas, so it’s important that responses are culturally informed, culturally appropriate and culturally safe.”

The research calls for new policy and funding strategies, with direct input from Aboriginal leaders to improve the coordination of housing, homelessness, and related services in urban communities.

One of the characteristics of Indigenous homelessness is the extent to which some people move between different forms of housing insecurity and homelessness, effectively cycling through the system rather than progressing through it towards long-term housing. Addressing their needs requires more housing and a more assertive approach to sustaining tenancies.

“Support for the wraparound care that Aboriginal community-controlled organisations can provide is critical, including co-designed programs and responses as part of self-determination,” Prof Tedmanson says.

“The very high rate of Indigenous incarceration is also a critical area for policy attention. There is insufficient coordination between specialist homeless services and the criminal justice system. A formal protocol for advising crisis accommodation services is needed, as is support for sustaining tenancies.

“It’s a circular solution. Stable housing improves mental and physical health and social and emotional wellbeing along with [reducing] substance abuse. Addressing these issues leads to more secure housing. In short, we need more culturally safe, accessible social housing for First Nations people,” Prof Tedmanson says.

New national council to help address housing issues

While the current housing crisis may appear intractable, dedicated research combined with initiatives such as the National Housing Supply and Affordability Council, mean progress is being made.

The Federal Government is establishing a National Housing Supply and Affordability Council as an independent statutory advisory body to inform the Commonwealth’s approach to housing policy. It will provide options to improve housing supply and affordability.

Prof Andrew Beer says the Council might be last year's most important and impactful housing announcement.

“Australia’s approach to the challenges of housing supply and affordability over the past decade could easily be described as ‘ramshackle’,” he says, in a Conversation article co-authored with a fellow researcher. “This has meant policies, interests and outcomes have clashed.

“A National Housing Supply and Affordability Council (NHSAC) promises to provide a shared resource on national targets, achievements, and milestones. It will be able to systematically report on these over time.

“What many of us don’t realise, is that a great majority of the housing statistics discussed in the media and used by policymakers are produced by advocacy groups, industry, governments and think tanks – each with their own agendas.

“The new housing council can cut through all this by providing the nation with a single, authoritative voice to advise, interpret and monitor change over time. It is a positive development because it will formalise the way advice is developed, and build on the transparency and independence of shared data.”

Dr Fotheringham says the NHSAC is being framed to comprehensively understand supply, demand and affordability.

“I’m delighted, as this is exactly what AHURI has recommended to the Government,” Dr Fotheringham says.

"Fixing our housing system challenges, and delivering better housing outcomes for all Australians, is a complex challenge. But the combination of high-quality evidence, and constructive engagement with policy decision makers, industry and sector leaders, creates a real opportunity to make a positive difference for Australian households.”

You can republish this article for free, online or in print, under a Creative Commons licence, provided you follow our guidelines.