“A lot of the time, we think about changes in housing based on technology and building practices, but the much bigger influence on our housing is actually social,” Dr Madigan says.

“A lot of the time, we think about changes in housing based on technology and building practices, but the much bigger influence on our housing is actually social,” Dr Madigan says.

“The car is a good example – it is something external to our homes that has shaped them immensely. If someone from 200 years ago were to come and look at our contemporary homes, they would be mystified by driveways and garages and the network of long commuter roads linking suburbs to jobs in the city.

“Equally, if someone from a future in which private cars had been replaced by a fleet of autonomous vehicles were to travel back to today, they might also be struck by the apparent ‘quaintness’ of our old-fashioned houses catering to our old-fashioned cars.

“Our homes are really the result of the needs of society, and they change as those needs change.”

The design of Australian homes is heavily influenced by Australia’s reliance on cars. Photo Maria Collado/Shutterstock.com

The design of Australian homes is heavily influenced by Australia’s reliance on cars. Photo Maria Collado/Shutterstock.com

So, in 2020, as Earth’s human population stares down a pandemic that has turned society inside out, it seems reasonable to suggest the homes we make in its aftermath might reveal a great deal about our collective response. An architecturally-minded anthropologist of the future might look back on our post-COVID residences and ask, ‘What sort of people were they? Did they learn anything from this crisis? Or did they bury their heads in the sand and repeat the past?’

We spoke to seven UniSA academics from a range of disciplines to consider the sorts of examples we might hope that hypothetical anthropologist would find.

The future is now

Director of the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI) Research Centre at UniSA, Dr Braam Lowies, believes there is one clear lesson from the events of 2020 that many people appear keen to embrace.

Director of the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI) Research Centre at UniSA, Dr Braam Lowies, believes there is one clear lesson from the events of 2020 that many people appear keen to embrace.

“Over the past few months, I think people have come to appreciate the difference between a house and a home,” Dr Lowies says. “A house is just a building, but a home is all about a person’s feelings and values, all about a sense of family and safety and peacefulness. I think that is something people have rediscovered, and something they don’t want to let go.”

While the giant social experiment of keeping the entire nation housebound for months has been challenging on many levels, by and large, the shift to working from home has proven effective, even empowering. For many businesses, productivity has sustained or even increased under lockdown, and there have also been widespread reports of families feeling closer through this difficult period.

“As an example, major retail banks have managed to improve their results with a large number of their staff working from home,” Dr Lowies says. “Even with all the technical processes involved with their businesses, they have moved forward while working from home, and if businesses like that can prove this arrangement is effective, then that really sets a precedent to follow.

“But, perhaps more importantly, people have found they enjoy working from home, and it has made them more engaged with both their work and their family.”

As they say, a gift once given is difficult to take away, and considering the extent to which working from home has been a success for both employers and employees, this genie may never find its way back into the bottle. If so, that may not only represent an opportunity to completely reinvent work, but also, suggests Dr Lowies, to completely reinvent home.

"A lot of people have realised they don’t want or need to be chained to the office, and this has huge implications for how we think about real estate,” he says.

“Increased remote working has the potential to revitalise regional areas, which were previously hindered by a lack of employment. People now have the opportunity to decentralise, to work remotely and move somewhere they can have more space, more peace, more quality of life.

“At the same time, breaking dependence on the office will mean some businesses no longer need to carry the significant expense of large CBD office buildings and can themselves decentralise. This would further boost regional economies and infrastructure, at the same time freeing up real estate in the city for housing, tourism and other cultural activities.”

Flexible lives, flexible housing

A key group that could lead any shift to a regional-remote lifestyle is Millennials. Born between early 1980s and the mid-1990s, this group has largely been locked out of home ownership in most urban centres and forced to rent much later into life than previous generations.

Now they’ve reached an age where they’re starting to have children, many Millennials are looking to move from their convenient-but-cramped inner-city apartments. While traditionally this would have meant beating a retreat to the suburbs and gritting through a long daily commute, since COVID-19, academics and industry observers have suggested the ‘new normal’ of work-from-home arrangements might ultimately see this group move further afield.

“Suburban living really emerged as a result of the need to be near the office,” Dr Lowies says. “Take that need away, and people have more options. They can make a home somewhere out of the rat race, which will be more affordable and more flexible, allowing them to create a residence that caters to both family life and work life.”

While for some a decentralised life would entail building something new from scratch, meeting the needs of a new generation also represents an opportunity to transform what is already standing, whether that be traditional housing or more imaginative, non-conventional options.

Researcher in resource-efficient building Adjunct Professor David Ness believes that a significant aspect of creating the houses of the future actually lies in recycling the buildings of the past.

Researcher in resource-efficient building Adjunct Professor David Ness believes that a significant aspect of creating the houses of the future actually lies in recycling the buildings of the past.

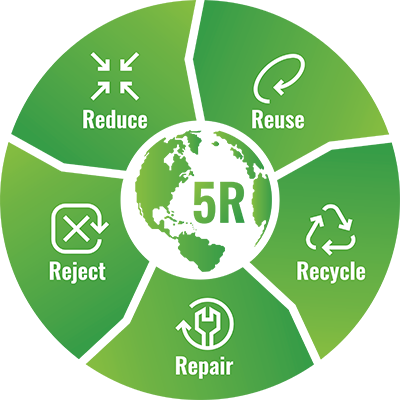

"The greenest, most resource efficient and lowest carbon building is the one that doesn’t need to be built,” Prof Ness says.

“So, if you can adapt existing assets, that is the best-case scenario – convert a factory into housing, or an office block into apartments.

“We need to shift our whole design philosophy away from ‘knock down and start again’ to ‘repurpose, reuse, recycle’, so that, as the activities or social needs in an area change, the buildings can also change to meet those needs.”

Extending this philosophy, Prof Ness and colleagues are developing a system that would see not just buildings, but also building components, repurposed and reused, maximising both resource efficiency and future adaptability.

“Whether reimagining old buildings or creating new assets, we must consider the energy and carbon ‘embodied’ in the production of building materials, and strive for smaller, adaptable houses,” Prof Ness says.

"Do we really need separate rooms for every purpose, which are empty much of the time? Or can we live comfortably within multi-purpose, shared and adaptable spaces, saving resources, carbon and cost?

“So, we should build walls that can be moved; create rooms that can be repurposed; develop designs that can be added to or subtracted from easily and elegantly. And we should aim to do it all with modular, reusable components that have a low carbon footprint, such as using plantation timber, which is actually a carbon sink as it ages.

“For safety and reliability, these reusable components need to be tracked over time, and as part of the ARUP Global Research Challenge, a UniSA team employed digital technologies to develop a prototype ‘cloud platform’ for identification, tracking, management and exchange of reusable, modular components over their extended life.”

While the repurpose-reuse approach to building could lead to the radical transformation of some areas – as witnessed in urban renewal programs currently underway in Adelaide – Dr Madigan suggests the same thinking could also help preserve the character of other areas.

Plant 4 Bowden (a retail hub) was previously a Clipsal warehouse and is an example of adaptive reuse. Photo by Dan Schultz and courtesy Renewal SA.

Plant 4 Bowden (a retail hub) was previously a Clipsal warehouse and is an example of adaptive reuse. Photo by Dan Schultz and courtesy Renewal SA.

“On the one hand, we could see lots of younger people moving to new locations and repurposing non-residential buildings into homes, which can add real vibrancy to a community,” he says.

“On the other hand, many older people don’t want to move from the community they’ve lived in for years, but they need to downsize and unlock some of the equity in their homes. I have been working with a number of South Australian councils to develop ways we can sympathetically reimagine large, traditional family homes so they can accommodate two or three separate residences for like-minded people.

“The advantage of this is that it retains the character and social connections of the neighbourhood while still accommodating changing needs of the community.

“A key part of this process is maintaining and developing shared gardens and outdoor areas for these new residences, which promotes social connectedness and protects urban greenspaces, some of which might have taken decades to establish.”

And if Millennials leave the city for the greener grass of regional Australia, it may well have a bump-on effect that ultimately leads to more ‘empty nesters’ becoming interested in downsizing the family home, as Dr Lowies suggests.

“If you get decentralisation of some workers and businesses, that would increase the availability of rental housing close to the CBD, meaning more students and young people could afford to live in the city – and move out of their parents’ homes.” Dr Lowies says.

Better homes, happier people

While social evolution might be the key driver of changing housing needs, technical advances also influence the range of possible responses to those needs, and nowhere is that more apparent than the area of energy sustainability.

"The carbon footprint of our houses is going to be one of the most important considerations for design and construction in the coming years,” Prof Ness says.

In housing, as in most other areas of climate discussion, there are two dimensions – mitigation and adaptation. On the one hand we must find ways to curb global warming by reducing the emissions output of the dwellings we develop; on the other, we must ensure those dwellings can cope with a hotter planet.

Dr Stephen Berry, a UniSA building scientist specialising in low-carbon, sustainable building design, says that while the challenges of mitigation and adaptation may seem separate, when it comes to housing, the responses to each are largely the same.

Dr Stephen Berry, a UniSA building scientist specialising in low-carbon, sustainable building design, says that while the challenges of mitigation and adaptation may seem separate, when it comes to housing, the responses to each are largely the same.

“The best practices to ensure the houses of the future are more resilient to extreme weather conditions are also the best practices for our current weather conditions – or the weather conditions of 10 years ago,” Dr Berry says.

“And if you do those things, that makes the house much more energy efficient, which in turn reduces its carbon footprint and may help reduce the climate problem.”

UniSA has a long history of housing efficiency research, starting with the work of Emeritus Professor Wasim Saman, who established the Sustainable Energy Centre in 1997, before becoming Research Leader in the CRC for Low Carbon Living, which operated from 2012 to 2019. The legacy of those projects is now carried on in UniSA’s Research Node for Low Carbon Living.

UniSA has a long history of housing efficiency research, starting with the work of Emeritus Professor Wasim Saman, who established the Sustainable Energy Centre in 1997, before becoming Research Leader in the CRC for Low Carbon Living, which operated from 2012 to 2019. The legacy of those projects is now carried on in UniSA’s Research Node for Low Carbon Living.

“The node has a wide range of researchers, but in many ways, we’re all disciples of Wasim,” Dr Berry says. “Building on the work he led for so many years, we now have some really strong data on what works, and why, in making a house more sustainable, and also on how sustainable houses contribute to a better quality of life.”

Integral to UniSA’s sustainable housing research has been extensive involvement with the Lochiel Park development, a purpose built ‘green village’ 8km from Adelaide’s CBD. Begun in 2004, and originally conceived as a demonstration project, Lochiel Park is now home to more than 150 residents and functions as a “national living laboratory” for low carbon research.

More than 150 residents live in Lochiel Park, 8km north-east of Adelaide’s CBD, which is a demonstration project for sustainable living.

More than 150 residents live in Lochiel Park, 8km north-east of Adelaide’s CBD, which is a demonstration project for sustainable living.

Dr Berry and colleagues at the Node for Low Carbon Living, including Dr David Whaley, continue to monitor a range of parameters at Lochiel Park. Dr Whaley, an electrical and electronic engineer, says the data from the project is invaluable.

Dr Berry and colleagues at the Node for Low Carbon Living, including Dr David Whaley, continue to monitor a range of parameters at Lochiel Park. Dr Whaley, an electrical and electronic engineer, says the data from the project is invaluable.

“It’s one thing to have projections or even lab tests, but to be able to gather data from real world situations over a long period of time has been a huge benefit to our research,” Dr Whaley says. “It’s allowed us to not only see how certain innovations perform, but also how residents interact with their properties.”

The biggest ongoing cost associated with housing, both to the planet and a resident’s bank balance, is thermal comfort – heating and cooling. The Node for Low Carbon Living has now amassed strong evidence that relatively simple passive design and building techniques can help maintain very stable temperatures in a home. And, in keeping with the adapt and upscale design philosophy, their research suggests achieving a low carbon home is often just as viable through retrofitting an existing property as it is through building a new one.

“The first basic principle of passive thermal stability is to insulate – everywhere,” Dr Berry says. “And, when you think you have insulated enough, insulate some more.”

Dr Berry says it is important to ensure insulation extends to every part of the house, including the roofing and windows, and he suggests no house in Australia should have anything less than double glazing on all glass areas.

“So, yes, you insulate the ceiling, which many people do already, but you also insulate the roof material, to stabilise the temperature in the roof cavity.

“And then you need to consider the windows, which many Australian buildings still don’t,” Dr Berry says. “Windows are a key area of heat transmission in a house, and proper thermally sealed double glazing can reduce this by 30 per cent; triple glazing can be up to 30 per cent better again.”

Another key aspect of a low carbon house is air-tight construction. Any passage of air from inside to outside or vice versa compromises the thermal integrity of a house, and Dr Whaley says the solution is as simple as filling all the gaps.

“Even tiny gaps between frames, which have traditionally been considered okay by many in the building industry, have to be closed,” he says.

As living proof, Dr Whaley recently built his own home according to the basic principles of energy efficiency, and he says that while the process required a little extra diligence, the results are outstanding.

“I had to work quite closely with the builders to ensure we reached the standard I was after, and a lot of it wasn’t things they were used to doing or aware of, but once it was introduced to them, they were all very keen to learn more, which is pretty encouraging.

“Now, even on a 40-plus day in summer, I don’t need to turn the air conditioning on, and so far this year, the heater hasn’t had to come on much either,” he says.

Perhaps most tellingly, Dr Whaley and Dr Berry’s research also suggests houses embracing sustainability principles not only offer financial and environmental benefits, they actually make for happier people.

"We now have the data to show that people moving into energy efficient housing consistently notice an improvement in their quality of life,” Dr Berry says.

“They are more comfortable in their daily activities, they sleep better, they have less anxiety about their carbon footprint and their energy bills, and the savings they make can be spent on the things they enjoy.”

A home for life

From where we live, to why and how we live there, a common theme seems to separate the recent past from a better future – the realisation that, when it comes to the place we call home, it’s not land value or designer upgrades that matter, but quality of life. In a technical sense, from Zoom to pink batts, everything we need to make that transition is already at hand – now, we just require the will to embrace the opportunity.

“Creating the house of the future really starts with creating the community of the future,” Dr Berry says. “And that largely means helping people understand how simple, and how beneficial, it can be to think of the big picture – to think ahead.”

Dr Madigan agrees.

“One thing that could make the places we live better in the future is if everyone involved in the housing system shared the same notion that houses are places to grow and live in for the long term, rather than something we want to sell for a profit in a few years’ time,” Dr Madigan says.

“This is a challenge when so much individual wealth is tied to property ownership and when so much of our rental housing stock is held by private investors, but it’s an ambition worth striving for.

“To realise it, we really need to plan for it from the outset. Too often the places we live in are seen as disposable, whether for taste or fashion or changing needs, we see them as temporary rather than something that can grow with us over 20 or 30 years. That needs to change.”

If, post-COVID, we do learn to place greater emphasis on the quality of life afforded by our residences and the communities in which they can exist – if we can come to value, as Dr Lowies suggested, “a sense of family, of safety and peacefulness” – then, perhaps, the anthropologist of the future might say we learned something very valuable from these challenging times.

They might say we stopped building houses and started building homes.

Earthship Ironbank – an eco bed & breakfast located in Ironbank in the Adelaide foothills.

Earthship Ironbank – an eco bed & breakfast located in Ironbank in the Adelaide foothills.

EARTHSHIPS AS BUSHFIRE (AND COVID-19) HAVENS?

For the past six months attention has been firmly fixed on COVID-19 but, as 2020 started, it was a disaster of a very different kind facing Australia – bushfires. The 2019/2020 summer saw unprecedented fires ravage the nation, raising serious questions about how a hotter, drier climate may change the way we live in the future.

Despite expert consensus suggesting there is probably no such thing as a ‘bushfire proof’ house in practice, there are techniques that can minimise the bushfire risk a residence faces, including non-flammable building materials, air-tight construction and double glazing. UniSA lecturer in sustainable design Dr Martin Freney believes many of the features desirable for bushfire resilience are already embodied in an existing design philosophy – Earthships.

Despite expert consensus suggesting there is probably no such thing as a ‘bushfire proof’ house in practice, there are techniques that can minimise the bushfire risk a residence faces, including non-flammable building materials, air-tight construction and double glazing. UniSA lecturer in sustainable design Dr Martin Freney believes many of the features desirable for bushfire resilience are already embodied in an existing design philosophy – Earthships.

"I believe homes and community buildings in bushfire-prone areas can be made much more fire-resistant by adopting earth-covered, off-grid structures – known as Earthships – as the new standard,” Dr Freney says.

Based on ideas of American architect Michael Reynolds, the typical Earthship features a number of inherent design features that make it extremely resilient in a bushfire.

“Houses sheltered by earth have a higher chance of survival in a bushfire, earth-based constructions are non-flammable,” Dr Freney says.

“A typical Earthship design has double-glazed windows to the north to let in winter sun, while mounds of earth, pushed up to roof level, protect the south, east and west walls. Bushfire building codes and standards already demand that windows have extra-thick, toughened glass to resist burning debris and intense heat, but double glazing offers extra protection.

“Also, underground pipes called earth-tubes or cooling tubes bring fresh air into the building at a nice temperature (better than outside) due to the heat-exchanging effect of the earth around the pipes. When wet fabric is placed over the end of the pipes, these can filter out bushfire smoke.

In addition to being physically resilient, Earthships are also self-sufficient, meaning they are not reliant on the grid to provide power for essential services during and after a bushfire emergency.

“Earthships have an electric pump powered by solar panels and a battery for day-to-day water supply – and to fight fires. Sprinklers can then spray water on any vulnerable areas regardless of grid failures and without needing to deal with the flammable fuel that petrol and diesel pumps require.”

Dr Freney suggests these features mean the Earthship design is not only more likely to survive in a bushfire but would also be quicker to recover from the situation, providing much needed infrastructure in impacted communities.

“As somewhere more or less intact after the disaster, still with power and clean flowing water, Earthships could be havens in the recovery phase after bushfires as well,” Dr Freney says. “And if there were a number of them in a community, this could function like a local support network for the area.

“In terms of the COVID-19 pandemic, a self-sufficient home with little to no running costs reduces the financial and emotional impact of occupants ‘trapped’ in their homes due to lock-downs and self-isolation.”

SOLAR – A GOOD PROBLEM TO HAVE

More than two million Australian households – more than 20 per cent – now have rooftop photovoltaic (PV) solar, and UniSA sustainable housing expert Dr Stephen Berry says such systems are a key component of the home of the future.

“In most circumstances, a house should have PV generation as a part of its energy solution,” Dr Berry says.

Based on current installation costs and common usage patterns, solar panels in Australia will pay for themselves within four to nine years, depending on where you live. With most panels warranted for at least 10 years and predicted to last at least 25 years, this is a pretty good return on investment.

However, the increased uptake of PV systems in Australia is also revealing a few challenges for the solar industry – but this could be easily addressed in future homes. A researcher with UniSA’s Research Node for Low Carbon Living, Kirrilie Rowe, says the key problem facing home PV lies in the discrepancy between the times of peak use and peak production.

“Solar panels on residential dwellings are typically installed facing the equator to maximise the energy collected, but the power generated by an equator-facing panel peaks at around midday, whereas residential loads typically have peaks in the morning and afternoon,” Rowe says.

At the moment, this discrepancy is partially offset by “feed in tariffs”, where households are paid for sending the energy they generate during the day into the grid. However, as the number of homes producing electricity increases, most of them will be sending it to the grid at the same time.

“In some markets at certain times, we’re already seeing over-supply during peak production times, which can cause voltage problems and reduce feed-in tariffs,” Rowe says. “The real challenge now facing the solar industry is finding ways to balance production and consumption.”

Offering one elegantly simple solution to this challenge, Rowe’s research explores how rethinking the orientation of rooftop solar panels might better match times of production to patterns of consumption, even if that means a slight reduction in overall energy generation.

“By orienting panels in different directions than just facing the equator, it’s possible to minimise the shortfall between load and generation,” Rowe says.

“This benefits the end-user by decreasing the amount of electricity required to be imported, and the stability of the grid by decreasing the amount of variability between peak and low loads.”

The other obvious solution to production-consumption problem is storage. UniSA STEM researcher and lecturer Vanika Sharma is exploring the viability of battery options for household solar. She says that while batteries will be the answer in the near future, price is currently prohibitive.

“There was a short period where, thanks to strong government subsidies in South Australia, a battery was economically viable for a household in this state, but as the subsidy has come down, this is no longer the case,” Sharma says.

“However, as battery technology improves and prices continue to fall, this will change, and my research is developing techniques for determining the optimal battery size for households and the best battery usage strategies to maximise energy efficiency.

“As the number of households generating their own energy increases, improving the rates of self-consumption becomes more crucial, and so energy storage technology and strategies will be an essential part of the house of the future.”