Ever since messages began to be encoded in digital form (binary digits – “bits”) over telephone wires to resolve the issue of noise interference associated with analogue signals, data has changed the world we live in.

Making sense of that transformation, or even understanding what happens to, and how much control we have, over our own data, is a challenge.

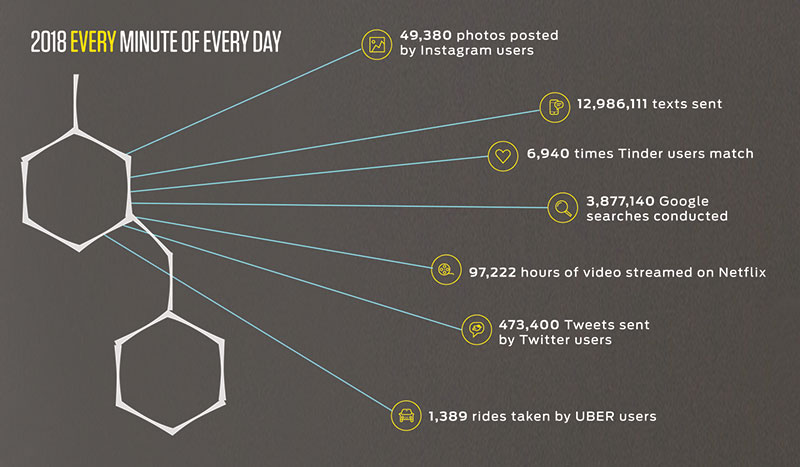

It’s estimated that 2.5 quintillion bytes of data are created each day; a wealth of information harvested from a range of connected devices that computer algorithms analyse, identify patterns within and feedback digestible insights about, in ways that continually enlighten and disrupt the world in which we live.

So what exactly is ‘big data’?

Dr Sanjay Mazumdar, CEO of the Data to Decisions Cooperative Research Centre (D2D CRC), which brings together researchers and industry to tackle the big data challenges facing Australia’s national security agencies, suggests size isn’t everything.

“People often get too caught up over the definitions of ‘big data’ and ‘small data’,” he says. “The real opportunity for organisations is to unlock value from the data that you have, irrespective of its size, and to use data that you don’t normally use.

“The term ‘big data’ doesn’t just refer to the amount (volume) of data. It is a term used to describe a collection of data sets so large and complex that it is difficult to process using traditional database management tools or data processing applications.”

The speed at which data is collected continues to increase, challenging organisations to find better ways to manage it.

Dean: Industry & Enterprise at the University of South Australia, Professor Andy Koronios, says these technological advances are truly transformative with the biggest changes yet to come.

“People have no idea just how fast technology is changing. In our lifetime we will see an entire transformation of our world,” Prof Koronios says.

“Over the past 60 years or so technology has been changing at a snail’s pace compared to what is about to happen.

“There are lots of guesstimates about the speed at which the knowledge information data repository of the world is increasing. At one time, it would have taken a 100 years to double. It may be only taking 18 months now and it is said that in a little while it will only be hours.”

He says this is a result of exponential improvements in computational power, computer storage and high-speed global connectivity.

“Fifty years ago the first integrated circuit (computer chip) had two transistors, 20 years later it had more than 2000 and cost the same price, today the Intel i7 processor is more than 300 billion times faster than the original chips. So our computation capacity will very soon reach the speed of the human brain.

“Storage too has had a dramatic reduction in space and cost. In 1956, computer storage of a few megabytes cost more than $100,000 and you needed a forklift to move it. Today we can get terabytes for $100 and this will keep growing. Soon we will be able to store all of Google’s data centres in something the size of a sugar cube.”

Prof Koronios, who recalls working with data stored in kilobytes on audio cassettes, says that living in the age of terabyte storage in a cloud means “we can now do the sorts of thing you just couldn’t have imagined in the past”.

The only limit is imagination

Dr Mazumdar believes the opportunity for all sectors to benefit from big data analytics is limited only by the imaginations of the people involved.

“The use of big data analytics powered by machine learning techniques is opening huge opportunities across all sectors. This ranges from yield forecasting in the agriculture sector through to identifying at-risk cancer patients from MRI scans.”

Data sources, statistical models and social media can be used to monitor and predict a pandemic, such as influenza.

The D2D CRC is doing groundbreaking work with cardiologists at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital using big data analytics to reduce cardiac complications.

“Applying machine learning to datasets from several cardiac procedures means risk factors can be identified, leading to improvements in patient outcomes,” Dr Mazumdar says.

In the US, IBM’s Watson for Oncology cognitive computing system is creating new ways to deliver bespoke care for patients with cancer by evaluating key data associated with their condition, linked with big data from relevant guidelines, best practices, medical journals and textbooks, to create personalised evidence-based treatment options for each patient.

Prof Koronios says there is value in exploring options to use cognitive computing systems such as IBM Watson Oncology for cancer research and other “grand challenges” in health and medicine.

Able to predict health issues better than your GP

“In the US, IBM’s Watson for Oncology is used in many hospitals – it can predict certain conditions in cancer far better than the best specialists in the world because it can ingest every single paper ever written about that specific area while also being guided in the beginning by those specialists,” Prof Koronios says.

“Cognitive computing is something that, given enough data, can actually surpass our diagnostic capabilities.

“If a computer knows your genome and phenomic characteristics, the results of all your medical tests as well as lifestyle data in terms of how you live, exercise and diet, then it can certainly predict medical outcomes that not even your own GP can, and that’s where the concept of personalised medicine comes in.”

Trading-in our personal data

Australia is implementing nationwide digital health records through the My Health Record system. It will detail, online, an individual’s key health information and enable millions of Australians to share that information with doctors, hospitals and other health-care providers from “anywhere, at any time”.

As of September 2018, 900,000 individuals had chosen to opt out of the database – highlighting concerns around privacy.

Data breaches regularly dominate the news, while Cambridge Analytica’s collection of the personal information of millions of Facebook users spooked many.

Even so, with more than 60 per cent of Australians still active on Facebook, it’s worth considering how much of our own information we willingly provide.

A mundane ‘like’ clicked on a Facebook post may not be very revelatory in itself – but add in another 149 ‘likes’ and, according to research undertaken at the universities of Cambridge and Stanford, an algorithm can judge your personality traits more accurately than your parents.

In the study, Computer-based personality judgments are more accurate than those made by humans, researchers compared the ability of people and computers to make judgments on personalities, describing the finding as an “emphatic demonstration” of the capacity of computers to discover an individual’s psychological traits through pure data analysis.

Prof Koronios says marketers are also good adopters of big data – connecting the dots and using insights that indicate preferences or habits.

“Marketers anticipate what you might want from the trail of data you have left across many areas and they are able to fuse that data,” he says.

“The reality is that you don’t know exactly where your name and details all are. We trade our privacy for peanuts – a discount here or there and you give them a lot of information and in bits – but a bit from here and there builds up – they can fuse that and then have a fantastic profile of you.”

In Yuval Noah Harari’s novel, A Brief History of Tomorrow, Harari spells out the drip feed exchange taking place:

“In the heyday of European imperialism, conquistadors and merchants bought entire islands and countries in exchange for coloured beads.

“In the 21st century our personal data is probably the most valuable resource most humans still have to offer and we are giving it to tech giants in exchange for email services and funny cat videos.”

In response to concerns about how personal data is shared, the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) came into force in May 2018 and has been heralded by the EU as the “most important change in data privacy regulation in two decades”, being designed to protect and empower EU citizen data privacy and reshape the way organisations approach data privacy.

“The concept of data ownership is a complex one,” Dr Mazumdar says.

“Instead the focus should be on how data is collected, stored and accessed and for what purpose.”

Using data as a personal scorecard

An altogether different purpose for data is the Social Credit System now being piloted in China. The use of facial recognition and geo-tracking coupled with personal data including academic, criminal and medical data, as well as data on individual online behaviour, will be fed into algorithms which will determine a social credit score for the country’s billion plus population.

With rewards for high scorers and punishments (including restricted travel) for low scorers, it’s a system which some have compared to the sci-fi TV series Black Mirror.

At UniSA’s Three Minute Thesis final in September, PhD student Jeff Ansah, from the School of Information Technology and Mathematical Sciences, spoke of predicting social disruption events including riots, strikes and demonstrations through the analysis of a broad range of data including keywords, trending hashtags and sentiment coupled with the use of smart computing.

Ansah’s research supervisor is Dr Wei Kang, a member of the D2D CRC’s Beat The News program, which aims to develop and use technology that will automatically and accurately measure the occurrence of future population-level events such as social disruption, political crises, election outcomes and disease outbreak.

“Being able to predict the future is the true power of big data analytics,” Dr Mazumdar says.

“Applying machine learning techniques to detect potential risky transactions or to identify areas to apply business focus, allows organisations to ‘get ahead of the curve’. The ability for computers to learn from the past and predict the future is the real game changer towards which big data practitioners are aiming.”

Getting ahead of the curve by anticipating election results, forecasting emerging trends in business or determining the spread of an infectious disease are just a few ways big data can be truly transformative, but they are countered by concerns over privacy and the ways in which such information can be used – and misused.

As the speed of transformation gathers pace, notions of artificial intelligence and technological singularity move from the realms of science fiction towards reality. When we consider what the future has in store for big data, perhaps it’s more relevant to ask, what does big data have in store for us?